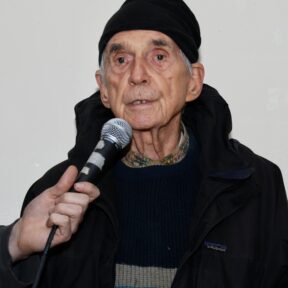

Daniel Berrigan

: Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: File: NLN Dan Berrigan 2008.jpg: Thomas GoodOverview

* Catholic priest and longtime anti-war activist

* Co-founded the Plowshares movement

* Communist apologist

* Supported the anti-capitalist Occupy Wall Street movement

* Died on April 30, 2016

Daniel Berrigan was born on May 9, 1921 in Virginia, Minnesota. He was the older brother of the late Philip Berrigan. The boys’ father, Thomas Berrigan, was a socialist farmer, railroad engineer, and radical labor organizer. The family moved to Syracuse, New York when Daniel was a child, and he was raised there.

After graduating from high school in 1939, Berrigan entered the order of Jesuits (at St. Andrew-on-the-Hudson Jesuit novitiate near Poughkeepsie, New York) to train for the priesthood and was ordained in June 1952. Soon after his ordination, the Church sent Berrigan to France, where he was influenced by the example of socialist priests who sought to express their religious faith through political activism and civil disobedience.

In 1954 Berrigan began teaching French and theology at the Jesuit-run Brooklyn Preparatory School in New York. He also led students in a project to help impoverished Puerto Ricans and blacks in New York City.

In 1957 Berrigan was appointed as a professor of New Testament Studies at La Moyne College, a Jesuit school in Syracuse. There, he led students in rent strikes and picketing on behalf of ghetto residents. Berrigan held that job until 1962.

In 1963 Berrigan attended the Christian Peace Conference in Prague, Czechoslovakia, which was replete with antiwar rhetoric. He then traveled to Russia, where he witnessed large-scale government persecution of Christians, and to South Africa, where the injustices of apartheid were evident everywhere. Berrigan later said that this trip overseas helped him understand “what it might cost to be a Christian,” and “what it might cost even at home, if things continued in the direction I felt events were taking.”

In 1964 Berrigan immersed himself in the civil-rights and antiwar movements. That same year, he and his brother Philip joined several members of the pacifist Catholic Worker Movement (including Thomas Merton) in founding the Catholic Peace Fellowship, which denounced the Vietnam War as immoral. (Daniel Berrigan credited Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker newspaper, for having shaped his thinking regarding the pacifist movement.) Also in ’64, Berrigan participated in the historic civil rights march at Selma, Alabama, and with Philip he signed a Declaration of Conscience publicly urging resistance to the military draft.

In 1965 Berrigan gained notoriety for defending the actions of one of his students at La Moyne College, David Miller, who became the first draft-card burner to be convicted under a 1965 law.

In ’65 as well, Berrigan—along with such notables as his brother (Philip) and William Sloane Coffin—was a founder of Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam .

Uneasy with Berrigan’s antiwar activism, Church leaders eventually assigned him to South America, where he reported for Jesuit Missions, a magazine he edited. As the Washington Post explains: “In 1965, Cardinal Francis Spellman, a supporter of the Vietnam War, told Father Berrigan’s Jesuit superiors to get the agitator out of New York City. He [Berrigan] was sent to South America, but seeing the conditions in the slums of Peru and made him more militant, not less. He believed the Catholic Church too often sided with the rich, and he criticized U.S. foreign policy supporting the sale of weapons to rightist military regimes.” But Catholic liberals in the U.S. demanded that Berrigan be brought back home, and within three months the Church relented.

In the fall of 1967 Berrigan moved to Ithaca, New York, where he continued his activism and helped direct Cornell University’s United Religious Work Program, the umbrella organization for all religious groups on campus; he would hold this post until 1970.

In October 1967 Berrigan was one of several hundred demonstrators arrested for taking part in an anti-war march on the Pentagon, making him the first U.S. priest ever arrested in such an event.

On the 27th day of that same month, Berrigan and three others (including his brother Philip) marched into the Selective Service office at the Customs House in Baltimore and dumped vials of animal blood (mixed with a small amount of their own blood) onto hundreds of draft records, to symbolically protest the spilling of human blood in Vietnam. Berrigan was arrested and charged with defacing government property and disrupting the Selective Service system.

In a 1968 exercise in anti-U.S. propaganda, Berrigan traveled to Hanoi with Tom Hayden and Howard Zinn to “accept” the release of three American prisoners of war. Later that year, he published Night Flight to Hanoi, an account of that experience.

Around that same time period, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called Berrigan a “traitor.”

On May 17, 1968, Berrigan and eight accomplices (including his brother Philip) raided the local draft-board office in Catonsville, Maryland. There, the “Catonsville Nine” took possession of hundreds of draft-board files, brought them outside to the parking lot, and set them ablaze with homemade napalm (a mixture of gasoline and soap chips). They then recited The Lord’s Prayer aloud and waited for the police to come and arrest them. (The Berrigan brothers were both dressed in their priestly vestments.) They also issued a statement to the press:

“We are Catholic Christians who take our faith seriously. We use napalm because it has burned people to death in Vietnam, Guatemala and Peru and because it may be used in American ghettoes. We destroy these draft records not only because they exploit our young men but also because they represent misplaced power concentrated in the ruling class of America. We believe some property has no right to exist. We confront the Catholic Church, other Christian bodies, and the synagogues of America with their silence and cowardice in the face of our country’s crimes.”

Soon thereafter, Berrigan wrote: “Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children. How many must die before our voices are heard, how many must be tortured, dislocated, starved, maddened? When, at what point, will you say no to this war?”

Berrigan was later sentenced to three years in prison for his destruction of government property in Catonsville. As the date when he and his brother were scheduled to report for prison—April 9, 1970—approached, the Berrigans decided instead to go underground in an effort to elude the law while continuing to spread their antiwar message. Both men’s names were promptly added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. Philip was found and arrested by FBI agents in St. Gregory’s Church in Manhattan on April 21, 1970. But Daniel managed to elude capture for about four months. On August 2, 1970, he appeared at a Methodist church and delivered a strong antiwar sermon. Nine days later, however, the FBI captured Berrigan in the Block Island home of the writer William Stringfellow and sent him to a correctional facility in Danbury, Connecticut.

The drama of the Catonsville incident and its aftermath elevated the Berrigan brothers to the status of icons of the Left.

During his incarceration, Berrigan was indicted by federal prosecutors as a co-conspirator in a scheme to abduct then-Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and put him on mock trial for war crimes. Berrigan was also indicted for participating in a plot that sought to blow up federal buildings in Washington, D.C. But because he was not a central player in that plot, he was acquitted and subsequently paroled from prison in January 1972, after which he resumed his activism.

In 1973 Berrigan became a member of Jonah House, a community of anti-war activists established that year by his brother Philip and the latter’s wife, Elizabeth McAlister. According to Jonah House, “The U.S. is the world’s #1 terrorist” and should “disarm now.”

When the fall of South Vietnam in 1975 triggered a mass exodus of refugees from that country, Berrigan was one of 81 prominent individuals to sign a May 30, 1979 open letter exhorting the North Vietnamese conquerors to treat their prisoners humanely. The popular singer Joan Baez published the letter in The New York Times.

Berrigan lauded Hanoi’s Communist prime minister Pham Van Dong as an individual “in whom complexity dwells … a face of great intelligence, and yet also of great reserves of compassion.”

In 1980 Berrigan and seven collaborators (including his brother Philip) created a nuclear arms abolitionist movement known as Plowshares, whose initial public act was to raid a General Electric plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, which manufactured nuclear missiles. There, the “Plowshares Eight” pounded missile casings with hammers in a symbolic attempt to “beat swords into plowshares” (a phrase from Biblical passages in Isaiah [2:4] and Micah [4:3]). They also poured animal blood onto some documents at the site. In 1981 Berrigan was sentenced to five-to-10 years in prison for his role in this action, but the sentence was eventually overturned.

Thereafter, Berrigan participated in many Plowshares demonstrations, consistently siding against American interests on every conceivable foreign-policy question. For instance, he opposed American intervention in Central America in the 1980s; the U.S. installation of Pershing missiles in West Germany in 1983; American aid to the Afghan rebels seeking to repel Soviet invaders in the ’80s; and U.S. military actions in Grenada, the Gulf War, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Berrigan was often arrested for his protest activities. Between 1970 and 1995, he spent a total of almost seven years in prison.

In his 1998 book, Daniel: Under the Siege of the Divine, Berrigan likened American foreign policy to the Holocaust: “The plain fact is that our nation, along with its nuclear cronies, is quite prepared to thrust enormous numbers of humans into furnaces fiercely stoked.”

In the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001, Berrigan stated that it would be wrong for America to respond militarily against those responsible for the calamity. “To work one’s way through that justification and sense of nationalism is the Christian task,” he said.

Attributing the 9/11 attacks directly to America’s abuse and exploitation of other nations, Berrigan characterized the Pentagon and the World Trade Center (the two principal targets of the terrorists) as symbols of idolatry and stated: “The ruin we have wantonly sown abroad has turned about and struck home…. Thus: sin, our sin, has shaken the pillars of empire. What has befallen, we have brought upon ourselves. The moral universe stands vindicated.” By contrast, Berrigan was loath to label the actions of the terrorists as evil. “Biblically speaking, that sort of language is blasphemous,” he said.

In 2002 Berrigan joined such notables as Amy Goodman, Michael Moore, and Michael Ratner in a “Vigil for Peaceful Tomorrows” symposium hosted by the anti-war group September 11th Families for Peaceful Tomorrows.

Berrigan was particularly critical of American military spending in the post-9/11 era. “This is money being pushed down a rat hole, and it’s bottomless,” he said in 2002. “… It will continue, as far as I can see, for the foreseeable future simply to lay waste to the land and the people, here and elsewhere, in the service of more kind[s] of indiscriminate killing.”

In 2006 Berrigan was arrested for participating in a demonstration at a naval museum in New York.

Maintaining that “the evils of capitalism are as real as the evils of militarism and the evils of racism,” Berrigan in 2011-12 supported the anti-capitalist Occupy Wall Street movement for displaying an “overriding sense of responsibility for the universe,” and for helping to “bring faith to the public and the public to the faith.”

Berrigan was also highly critical of America’s strongest ally, Israel. On various occasions he stated, for instance, that the Jewish state was, like the U.S. and South Africa, seeking “a biblical justification for crimes against humanity”; that “in place of Jewish prophetic vision,” Israel had unleashed “an Orwellian nightmare of double talk, racism, [and] fifth-rate sociological jargon, aimed at proving its racial superiority to the people it has crushed”; that Israel’s “military-industrial complex” closely resembled that of the United States; that while “Israel has not freed the captives, she has expanded the prison system, perfected her espionage, [and] exported on the world market that expensive blood-ridden commodity, the savage triumph of the technologized West, violence and the tools of violence”; and that “many American Jewish leaders were capable of ignoring the Asian holocaust in favor of economic and military aid to Israel.”

Aside from his terms of service at Le Moyne College and Cornell University, Berrigan at various times in his life also taught at Fordham University, the University of Detroit, Loyola University New Orleans, DePaul University, and UC Berkeley. He memorialized his reflections on his career as a war resister in more than 50 books of essays and poetry, some of which were co-authored by others.

On April 30, 2016, Berrigan died of a cardiovascular ailment in a Jesuit residence at New York’s Fordham University.

Further Reading: “Daniel Berrigan” (YourDictionary.com, Keywiki.org); “Daniel J. Berrigan, Pacifist Priest Who Led Anti-War Protests, Dies at 94” (Washington Post, 4-30-2016); “Jesuit Priest and Peace Activist … Daniel Berrigan Dies at 94” (Los Angeles Times, 4-30-2016); “Father Daniel Berrigan Obituary” (The Guardian, 5-2-2016); “The Life and Death of Daniel Berrigan” (Common Dreams, 5-2-2016); “Daniel Berrigan: America’s Street Priest” (Common Dreams, 6-11-2012); “Daniel Berrigan, SJ” (IgnatianSpirituality.com).