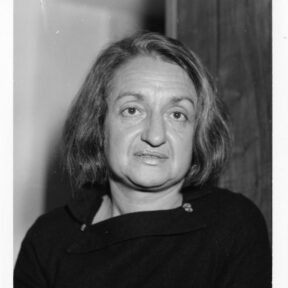

Betty Friedan

: Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: Smithsonian Institution from United StatesOverview

* Author of The Feminine Mystique

* Co-founder of the National Organization for Women

* Onetime member of the Young Communist League

* Longtime veteran of professional journalism in the Communist Left

* Referred to the American household as “a comfortable concentration camp”

* Co-founded the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws, which would later change its name to NARAL Pro-Choice America

* Died in 2006

Family Life

Betty Friedan was born Bettye Naomi Goldstein on February 4, 1921, in Peoria, Illinois, where she was raised by her parents as a secular Jew. Her father, an immigrant from Russia, was a jewelry store owner; her mother, the daughter of Hungarian Jews, quit her job as the women’s-page editor of a newspaper and stayed home to raise her children. Later in life, Betty (henceforth, Friedan) would explain that her mother had “loved” her newspaper job, “but in that era married women didn’t work.” Friedan also described her mother as someone who had suffered from “impotent rage” because, without the option of pursuing a career, she could find “no place to channel her terrific energies.” “She [the mother] made our life so miserable,” Friedan wrote in her 2000 memoir, Life So Far, because “she was so miserable herself.”

Communist Influences in Higher Education & Journalism

In 1938 Friedan enrolled as a freshman at Smith College, a private liberal-arts school for women in Northampton, Massachusetts. Growing ever-more active politically, she soon aligned herself with the American Communist Left. In particular, she took an interest in literature about the Spanish Civil War, and in Communist John Reed’s famous account of the 1917 Russian October Revolution, Ten Days That Shook the World.

In 1940 Friedan enrolled in an economics course taught by Communist Party USA member Dorothy Wolff Douglas, who would go on to have an immense influence on Friedan’s worldview. In 1940 as well, Friedan became an outspoken champion of the Popular Front strategy that sought to strengthen the Communist movement by aligning it with a broad range of radical and liberal organizations, rather than having it remain an isolated entity. First adopted in 1935, the Popular Front framed its agendas in terms of the fundamental values of the societies that the Communists intended to take over. In place of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” and an “international civil war,” for example, the Communists organized coalitions for “democracy, justice, and peace.” Nothing had changed in the philosophy and goals of the Communists, but by appearing to advocate respectable and widely shared goals, they were able to forge broad alliances with individuals and groups that: (a) had no inkling of the Communists’ true agendas, or (b) believed those agendas to be far less sinister than they actually were. By working through the Popular Front which they had formed with liberal groups, the Communists were able to hide their conspiratorial activities and increase their own numbers until they became a formidable political force.

Former Smith College history professor Daniel Horowitz, in the course of doing research for his 1996 book Rethinking Betty Friedan and The Feminine Mystique, studied Friedan’s notes from her college days and reported on the positive impression that Friedan clearly was developing about life in the Soviet Union:

“Especially important is what [Friedan] recorded when [Professor Dorothy Wolff] Douglas talked about the condition of women in Nazi Germany and the USSR. On [Friedan’s] twentieth birthday, in February 1941, Douglas mentioned what she called the ‘feminist movement.’ She talked about the ‘traditionalism’ of the Nazis’ attitude to religion, women, children, and family. According to [Friedan’s] notes, Douglas said the Nazis placed children at the center of family lives, celebrated motherhood, and opposed women working outside the house in professional positions (not as farmers and mutual laborers). They minimized the intellectual capacity of women, emphasizing instead the importance of their feelings. In the middle of her lecture on women under Nazi rule, Douglas noted parenthetically that men who controlled women’s magazines participated in this conscious ideological effort to tell women that despite their aspirations for intellectual life, in fact they were instinctual being who belonged in the home. In contrast, Douglas said, women in the USSR experienced equality of opportunity, with their wages almost matching (and in some cases exceeding) those of men.”

Friedan joined the Young Communist League (the youth branch of the Communist Party) and attempted to join the Party itself at least twice. She recorded in her memoir that she had first explored the possibility of joining the Party in 1942, but had decided against it after discussing the matter with her father. Her FBI file recorded yet another attempt to joint the Party in 1944, when she was turned away because “there already were too many intellectuals in the labor movement and … she would have greater party influence by staying in her own field, which is Psychology.”

After graduating summa cum laude with a psychology desgree from Smith College in 1942, Friedan won a fellowship for graduate studies in that same field at UC Berkeley. At that time, Friedan harbored what she would later describe as a “romantic vision of communism” and a perception of herself “as a revolutionary.” Indeed, she embraced without reservation the Communist belief that the American principles of “democracy, civil liberties and freedoms of conscience and speech” were merely “a capitalist mask for oppression,” and she viewed military conflicts mostly as by-products of the greed of capitalist weapons manufacturers pursuing endless profits.

Friedan did one year of graduate work (1942-1943) at Berkeley, where she became intimately involved with a young Communist physicist, David Bohm, who was working on atomic bomb projects with J. Robert Oppenheimer. “Bohm would later invoke the Fifth Amendment while testifying in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee,” writes Carey Roberts at iFeminists.com, “and leave the United States shortly thereafter.

Also at Berkeley, Friedan studied under the renowned psychologist Erik Erikson, among others.

Friedan then won an even more prestigious fellowship from UC Berkeley but turned it down, as she would recount in an interview many years later: “And then I won a really big fellowship to go straight on to get my Ph.D. for the next three or four years. And I went through agonies of indecision, and then I decided not to accept it. I just decided I didn’t want to be an academic.”

In 1943, Friedan began a nine-year stint working as a labor journalist. The first three of those years were spent with Federated Press, a leftwing news service established by members of the Socialist Party. Then, for approximately six years beginning in July 1946, she worked as a reporter for UE News, the newspaper of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) — one of the most radical labor unions in America. Historian Ronald Schatz described the UE as “the largest Communist-led institution of any kind in the United States.” Among Friedan’s assignments at UE News was to promote the Communist-run Progressive Party presidential campaign of Henry Wallace in 1948.

As the Marxist-turned-conservative author David Horowitz has pointed out, Friedan was a longtime “veteran of professional journalism in the Communist Left, where she had been thoroughly indoctrinated” in the notion that American women were “oppressed.” “[F]rom her college days and until her mid-thirties,” adds Horowitz, Friedan “was a Stalinist [M]arxist (or a camp follower thereof) … [S]he was certainly familiar with the writings of Engels, Lenin, and Stalin on the subject [of women] and had written about it herself as a journalist for the official publication of the communist-controlled United Electrical Workers union.”

Marriage & Children

In 1947 Friedan — i.e., Betty Goldstein[1] — married Carl Friedan, a theater director who later became an advertising executive. For the first five years of her marriage, Friedan kept her job with UE News while raising her three children, who were born in 1948, 1952, and 1956, respectively.

The Feminine Mystique

In 1957, Friedan, who was working at that time as a freelance writer for various women’s magazines, attended the 15-year reunion of her Smith College graduating class. One of the magazines for which she was writing, asked her to get in touch with her former female classmates sometime after the reunion and have them respond to a questionnaire about the trajectory their lives had taken since graduation. Friedan did in fact contact many of them, and based on the results of her surveys, she penned an article that appeared in McCall’s, Redbook, and Ladies’ Home Journal. In that piece, Friedan alleged that most of her former classmates had gone on to become disillusioned suburban housewives suffering from a “nameless, aching dissatisfaction” that she would eventually call “the problem that has no name.”

When Friedan subsequently sent the same questionnaire to graduates of Radcliffe and other colleges, and also interviewed scores of women personally, she got essentially the same results, leading her to suspect that a deep sense of discontent was widespread among American women. Pursuing the theme still further, Friedan went on to spend a total of five years interviewing mostly white, middle-class women across the United States.

Sometime around 1959, Friedan copied into her notes the following quote from Friedrich Engels’ famous 1884 essay, The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State: “The emancipation of women becomes possible only when women are enabled to take part in production on a large, social scale, and when domestic duties require their attention only to a minor degree.”

Friedan completed her book in 1963 and published it under the title The Feminine Mystique. Its main assertion was that women as a class were victimized not only by many forms of discrimination, but also by the socially transmitted message that they could find a sense of identity and fulfillment only by living vicariously through their husbands and children — while sublimating their own desperate aspirations to be something other than wives and mothers. Women, Friedan explained, had been raised to imbibe the myth of the “feminine mystique,” which taught them that the “highest value” they could pursue was the “fulfillment of their own femininity” as housewives and mothers, and the eschewing of careers outside the home. But such a life, by Friedan’s telling, prevented women from finding true meaning and satisfaction. “The core of the problem for women,” she wrote, is a “problem of identity—a stunting or evasion of growth that is perpetuated by the feminine mystique.” Friedan maintained that each woman had to solve her own “identity crisis” by finding “the work, or the cause, or the purpose that evokes … creativity.” And “the only kind of work which permits” a woman “to realize her abilities fully, to achieve identity in society,” Friedan wrote, is “the lifelong commitment to an art or science, to politics or profession.” Absent such a commitment, women were doomed to be “trapped in endless and empty housewifery” and suffer from a “nameless aching dissatisfaction.”

Also among the book’s noteworthy quotes were the following:

- “[T]he women who ‘adjust’ as housewives, who grow up wanting to be ‘just a housewife,’ are in as much danger as the millions who walked to their own death in the concentration camps—and the millions more who refused to believe that the concentration camps existed.”

- “In fact, there is an uncanny, uncomfortable insight into why a woman can so easily lose her sense of self as a housewife in certain psychological observations made of the behavior of prisoners in Nazi concentration camps. In these settings, purposely contrived for the dehumanization of man, the prisoners literally became ‘walking corpses.’ Those who ‘adjusted’ to the conditions of the camps surrendered their human identity and went almost indifferently to their deaths. Strangely enough, the conditions which destroyed the human identity of so many prisoners were not the torture and the brutality, but conditions similar to those which destroy the identity of the American housewife.”

- “All this seems terribly remote from the easy life of the American suburban housewife. But is not her house in reality a comfortable concentration camp?… The work they do does not require adult capabilities; it is endless, monotonous, unrewarding. American women are not, of course, being readied for mass extermination, but they are suffering a slow death of mind and spirit.”

- “If we continue to produce millions of young mothers who stop their growth and education short of identity, we are committing quite simply genocide, starting with the mass burial of American women and ending with the progressive dehumanization of their sons and daughters.”

- “A massive attempt must be made by educators and parents—and ministers, magazine editors, manipulators, guidance counselors—to stop the early-marriage movement, stop girls from growing up wanting to be ‘just a housewife.’”

Below is an extended edited excerpt from The Feminine Mystique, wherein Friedan describes the quiet desperation that, by her telling, so many American housewives and mothers felt without careers in the business world:

“The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the 20th century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night – she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question – ‘Is this all?’

“Over and over women heard in voices of tradition and of Freudian sophistication that they could desire no greater destiny than to glory in their own femininity. They were taught to pity the neurotic, unfeminine, unhappy women who wanted to be poets or physicists or presidents. They learned that truly feminine women do not want careers, higher education, political rights – the independence and the opportunities that the old-fashioned feminists fought for. Some women, in their 40s and 50s, still remembered painfully giving up those dreams, but most of the younger women no longer even thought about them. A thousand expert voices applauded their femininity, their adjustment, their new maturity. All they had to do was devote their lives from earliest girlhood to finding a husband and bearing children.

“Fulfilment as a woman had only one definition for American women after 1949 — the housewife-mother. As swiftly as in a dream, the image of the American woman as a changing, growing individual in a changing world was shattered. Her solo flight to find her own identity was forgotten in the rush for the security of togetherness. Her world shrank to the cosy walls of home.

“In the 15 years after the second world war, this mystique of feminine fulfillment became the cherished and self-perpetuating core of contemporary American culture. Words like ’emancipation’ and ‘career’ sounded strange and embarrassing; no one had used them for years. […]

“If a woman had a problem in the 1950s and 1960s, she knew that something must be wrong with her marriage, or with herself. Other women were satisfied with their lives, she thought. What kind of a woman was she if she did not feel this mysterious fulfilment waxing the kitchen floor? She was so ashamed to admit her dissatisfaction that she never knew how many other women shared it. If she tried to tell her husband, he didn’t understand what she was talking about. She did not really understand it herself.

“No other road to fulfilment was offered to American women in the middle of the 20th century. Most adjusted to their role and suffered or ignored the problem that has no name. It can be less painful for a woman not to hear the strange, dissatisfied voice stirring within her.

“Gradually I came to realise that the problem that has no name was shared by countless women in America. Just what was this problem that has no name? What were the words women used when they tried to express it? Sometimes a woman would say ‘I feel empty somehow … incomplete.’ Or she would say, ‘I feel as if I don’t exist.’ Sometimes she blotted out the feeling with a tranquilliser. Sometimes she thought the problem was with her husband or her children, or that what she really needed was to redecorate her house or move to a better neighborhood, or have an affair, or another baby.

“If I am right, this problem stirring in the minds of so many American women today is not a matter of loss of femininity or too much education, or the demands of domesticity. It is far more important than anyone recognises. It may well be the key to our future as a nation and a culture. We can no longer ignore that voice within women that says: ‘I want something more than my husband and my children and my home.’

“The problem that has no name — which is simply the fact that American women are kept from growing to their full human capacities — is taking a far greater toll on the physical and mental health of our country than any known disease. If we continue to produce millions of young mothers who stop their growth and education short of identity, without a strong core of human values to pass on to their children, we are committing, quite simply, genocide, starting with the mass burial of American women and ending with the progressive dehumanisation of their sons and daughters. These problems cannot be solved by medicine or even by psychotherapy.

“A woman today who has no goal, no purpose, no ambition patterning her days into the future, making her stretch and grow beyond that small score of years in which her body can fill its biological function, is committing a kind of suicide. The feminine mystique has succeeded in burying millions of American women alive. There is no way for these women to break out of their comfortable concentration camps except by finally putting forth an effort — that human effort which reaches beyond biology, beyond the narrow walls of the home, to help shape the future. We need a drastic reshaping of the cultural image of femininity that will permit women to reach maturity, identity, completeness of self, without conflict with sexual fulfilment.”

What Friedan did not mention in The Feminine Mystique was her longstanding alliance with the Communist Left. Instead, she depicted herself as an average, apolitical housewife who never previously had given any thought to the status of women in society.

An almost instant best-seller, The Feminine Mystique sold 1.4 million copies in just its first printing. The book essentially ignited the so-called “Second Wave” of feminism.

National Organization for Women

In October 1966 Friedan co-founded the National Organization for Women, and she served as the group’s president until March 1970. Friedan also helped to write NOW’s charter, and to lead its lobbying efforts aimed at pressuring the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to clamp down on sex discrimination.

Writers and Editors War Tax Protest

In 1967 Friedan signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to withhold tax payments as an act of protest against the Vietnam War.

NARAL & Abortion Rights

In 1969 Friedan helped establish the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws, which would later change its name to the National Abortion Rights Action League, and then to NARAL Pro-Choice America. Viewing the right to abortion as “a final essential right of full personhood,” Friedan at a 1969 abortion convention stated that “motherhood is a bane almost by definition,” and that abortion rights were necessary in order to ensure women’s opportunity to achieve “self-determination and full dignity” through fulfilling careers in the workplace.

Divorce

Also in 1969, Friedan and her husband Carl divorced.

Women’s Strike for Equality

Friedan helped organize the August 26, 1970 “Women’s Strike for Equality” in New York City, where many thousands of women followed her in a march down Fifth Avenue, carrying signs and banners that bore such slogans as “Don’t Cook Dinner — Starve a Rat Tonight!” and “Don’t Iron While the Strike Is Hot.” The NOW-sponsored event was held on the 50th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed women the right to vote.

National Women’s Political Caucus

In 1971, Friedan was a founding member of the National Women’s Political Caucus.

First Women’s Bank & Trust Company

In 1973, Friedan became director of the First Women’s Bank and Trust Company.

Equal Rights Amendment

In the 1970s as well, Friedan led the (unsuccessful) campaign to ratify the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Social Policies Promoted by Friedan

- Divorce: Friedan called for the enactment of “no fault” divorce-on-demand, where either party could unilaterally dissolve a marriage at any time.

- Contraception & Abortion: Friedan said that contraception enabled women “to take control of their bodies” and “define themselves by their contribution to society, not just in terms of their reproductive role.”

- Sex Discrimination: As Scott Yenor writes for The Heritage Foundation: “Under Friedan’s leadership, NOW … complained that stewardesses were fired when they were no longer attractive, that newspaper advertisements asked for applications from only one sex, that companies prohibited women from performing dangerous or high-level work, and that men’s clubs prohibited the entry of women. In each of these cases and in many others, NOW gained the EEOC’s attention, and companies were required to change their practices under threat of legal penalty…. Companies would soon have to take affirmative action to secure a sufficient number of women to ensure immunity from charges of discrimination. NOW set up a task force on education that called for public instruction in family planning, the elimination of sex-specific school curricula, and the integration of student facilities such as dormitories on college campuses…. Education should instead be gender-neutral and treat boys and girls the same. NOW also called for opening up the priesthood to women and the removal of sex segregation in religious organizations and church-sponsored schools in the hope that private organizations could be pressured to abandon their commitment to the feminine mystique.”

- Government Child Care: On the premise that women could not achieve equality without government-provided child care to free them from the shackles of motherhood and allow them to pursue some type of creative vocation outside the home, Friedan and NOW in 1967 demanded “paid maternity leave, federally mandated child care facilities, and a tax deduction for home and child care expenses for working parents.”

- Gender-Neutral Society: Friedan favored a gender-neutral society as a means of addressing disparities between the sexes — disparities allegedly due to societal discrimination and the intransigence of the so-called feminine mystique.

Co-founder of the Campaign for America’s Future

In 1996, Friedan was one of the 130 leftists who collaborated to co-found the Campaign for America’s Future.

Books

Friedan published several books during the course of her life, including It Changed My Life: Writings on the Women’s Movement (1976); The Second Stage (1981); The Fountain of Age (1993); Beyond Gender (1997); and her memoir, Life So Far (2001).

Political Donations

Friedan gave occasional donations to Democratic political candidates (Carl Levin, Bill Bradley, Daniel Patrick Moynihan) and leftwing organizations (EMILY’s List, the Democratic National Committee, and the Hollywood Women’s Political Committee).

Death

Friedan died of congestive heart failure on February 4, 2006, her 85th birthday.

Footnotes:

- By 1942, Bettye Goldstein had dropped the final “e” from her first name, because she viewed it as an unnecessary affectation conceived by her mother.

Additional Resources:

The Marxist Roots of Feminism

By Spyridon Mitsotakis

August 29, 2011

Betty Friedan and the Birth of Modern Feminism

By The Heritage Foundation

October 12, 2018

Feminism’s Dirtiest Secret

By David Horowitz

June 9, 2000

Betty Friedan’s Secret Communist Past

By David Horowitz

January 18, 1999

The Untold Story of Betty Friedan

By Carey Roberts

November 25, 2003

Reconsiderations: Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique”

By Christina Hoff Sommers

September 17, 2008

What Moderate Feminists?

By Carol Iannone

June 1, 1995

BOOK:

Betty Friedan and the Making of “The Feminine Mystique”: The American Left, the Cold War, and Modern Feminism

By Daniel Horowitz