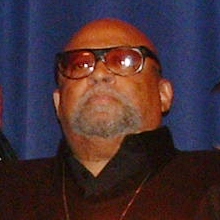

Maulana Karenga

: Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: Apavlo at English WikipediaOverview

* Marxist activist and black nationalist

* Founder of the militant Black Power organization United Slaves

* In 1971, he was arrested for assaulting and torturing two female members of his organization.

* Professor and chairman of the Department of Black Studies at California State University, Long Beach

* Creator of the “African American” holiday, Kwanzaa

Radical Roots

Maulana Ndabezitha Karenga was born as Ronald McKinley Everett on July 14, 1941 in Parsonsburg, Maryland. He was one of 14 children, and his father was a Baptist minister and tenant farmer.

At age 18, Everett moved to Los Angeles and became active in the civil rights movement. After receiving an associate’s degree at Los Angeles Community College, he went on to earn both a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree at UCLA. One of Everett’s mentors at UCLA was the Jamaican anthropologist Councill Taylor, a Negritudist who preached that traditional black cultures are superior to their European counterparts.

In the early to mid-1960s, Everett changed his name to Maulana Karenga. (“Maulana” is Swahili-Arabic for “master teacher,” and “Karenga” is Swahili for “keeper of tradition.”) Karenga quickly established himself as a major figure in the Black Power movement and as a leading “cultural nationalist”—a term that in the ’60s served to distinguish Karenga and his followers from the Black Panthers, who were conventional Marxists.

After the infamous Watts riots of 1965, Karenga helped create the Black Congress, an umbrella group consisting of numerous radical organizations in South-Central Los Angeles. He also helped set up Black Power conferences in several major American cities.

In 1965 as well, Karenga co-founded (with Hakim Jamal) the militant Black Power organization, United Slaves (US), which advocated for a black cultural revolution and the proliferation of independent black schools, African-American Studies departments, and black student unions. In Karenga’s words, United Slaves aimed to “provid[e] a philosophy, a set of principles, and a program which inspire a personal and social practice that not only satisfies human need but transforms people in the process, making them self-conscious agents of their own life and liberation.”

Creating Kwanzaa

In 1966 Karenga created Kwanzaa, a holiday that urged the establishment of a separate and independent political structure exclusively for African Americans. This holiday is celebrated each year from December 26 through January 1, and its name is a Swahili term meaning “first fruits.” Kwanzaa’s origins lie in the so-called “first harvest celebrations of Africa,” which, according to the Black Storytellers Alliance, “are recorded in African history as far back as ancient Egypt and Nubia.”

It is unclear, however, why ancient Egyptians or Nubians might have held harvest festivals shortly after the winter solstice, or what crops they would have harvested. And though Kwanzaa celebrants are instructed to use maize in their holiday rituals, maize is a New World plant that did not exist in ancient Africa. As journalist Tony Snow observed in 1999: “Kwanzaa ceremonies have no discernible African roots. No culture on earth celebrates a harvesting ritual in December, for instance … Even the rituals using corn don’t fit. Corn isn’t indigenous to Africa. Mexican Indians developed it, and the crop was carried worldwide by white colonialists.”

Claiming that Kwanzaa is rooted in “the best in nationalist, Pan-Africanist, and socialist thought,” Karenga has explained: “I created Kwanza … to reaffirm our rootedness in African culture and the fact that as Africans we come together to reinforce the bonds between us as a world African community. And to celebrate the meaning and beauty of being African in the world.” In his 1977 book Kwanzaa: Origins, Concepts, Practice, Karenga wrote that the holiday offered black people “an opportunity to celebrate themselves and history rather than simply imitate the practice of the dominant society.”

According to The Official Kwanzaa Web Site, Karenga’s holiday was created to: (a) “reaffirm the communitarian vision and values of African culture and to contribute to its restoration among African peoples in the Diaspora”; (b) serve as “an act of cultural self-determination, as a self-conscious statement of our own unique cultural truth as an African people”; (c) foster “conditions that would enhance the revolutionary social change for the masses of Black Americans”; and (d) provide a “reassessment, reclaiming, recommitment, remembrance, retrieval, resumption, resurrection and rejuvenation of those principles (Way of Life) utilized by Black Americans’ ancestors.”

Kwanzaa arose out of a cultural philosophy, devised by Karenga, called Kawaida—a Swahili term for “tradition” and “reason.” According to Karenga, Kawaida incorporates the “best of early Chinese and Cuban socialism,” and its adherents believe that one’s racial identity “determines life conditions, life chances and self-understanding.” When he was asked to distinguish Kawaida from “classical Marxism,” Karenga essentially said that, under Kawaida, race-based divisions and animosities are every bit as important as those that, in the Marxist tradition, are class-based. That response was consistent with Tony Snow’s 1999 observation that: “The inventors of Kwanzaa weren’t promoting a return to roots; they were shilling for Marxism. They even appropriated the term ‘ujima’ [meaning ‘collective work’], which [the African socialist] Julius Nyrere cited when he uprooted tens of thousands of Tanzanians and shipped them forcibly to collective farms, where they proved more adept at cultivating misery than banishing hunger.”

Karenga billed his new Kwanzaa holiday as an alternative to Christian, Jewish, and Islamic traditions. Indeed, he explained that his creation of Kwanzaa was motivated in part by hostility toward both Christianity and Judaism. In his 1980 book, Kawaida Theory, Karenga claimed that Western religion “denies and diminishes human worth, capacity, potential and achievement.” “In Christian and Jewish mythology,” he added, “humans are born in sin, cursed with mythical ancestors who’ve sinned and brought the wrath of an angry God on every generation’s head.”

Karenga once described Kwanzaa as “an oppositional alternative to the spookism, mysticism and non-earth based practices which plague us as a people.” On another occasion, he characterized Christianity as a “belief in spooks who threaten us if we don’t worship them and demand we turn over our destiny and daily lives” to them. Such a belief system, Karenga asserted, “must be categorized as spookism and condemned.”

Contrary to traditional monotheism, Kwanzaa, like Marxism, worships no god at all. Rather, Kwanzaa deifies people and their ancestors. It substitutes faith in the self and in the collective, for faith in a divine creator.

After he established Kwanzaa, Karenga exhorted his followers to abide by the “Nguzu Saba,” or the “Seven Principles of Blackness.” Rooted in the socialist precepts of parity, collectivism, class consciousness, identity politics, and proletarian unity, those principles include:

- Umoja (Unity): “to strive for and maintain unity in the family, community, nation and race”

- Kujichagulia (Self-Determination): “to define ourselves, name ourselves, create for ourselves and speak for ourselves” (i.e., race-consciousness and identity politics)

- Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility): “to build and maintain our community together and make our brother’s and sister’s problems our problems, and to solve them together” (i.e., socialism and groupthink)

- Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics): “to build and maintain our own stores, shops and other businesses and to profit from them together” (code for “buy black”); Karenga describes this principle as “essentially a commitment to the practice of shared social wealth”—a euphemism for communism.

- Nia (Purpose): “to make our collective vocation the building and development of our community in order to restore our people to their traditional greatness” (i.e., identity politics)

- Kuumba (Creativity): “to do always as much as we can, in the way we can, in order to leave our community more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited it”

- Imani (Faith): “to believe with all our heart in our people, our parents, our teachers, our leaders and the righteousness and victory of our struggle”

Notably, the Seven Principles enumerated above were precisely the same as those espoused by the Symbionese Liberation Army, the pro-Marxist terror organization that famously kidnapped the heiress Patricia Hearst in the 1970s.

As a tangible symbol of his seven Principles of Blackness, Karenga appropriated the menorah from Judaism and renamed it with the Swahili word kinara, a candle holder bearing Kwanzaa’s trademark colors of red, black, and green (one blacked candle flanked by three red candles and three green candles). This color scheme was borrowed from Marcus Garvey’s old flag of black nationalism, with black representing the black race, red signifying the blood shed by African people in their quest for liberation, and green connoting the pristine splendor of Africa’s landscapes.

Questions have arisen as to why Karenga elected to use Swahili words for the major principles and objects associated with Kwanzaa—given that American blacks are primarily descended from people who came from Ghana and other parts of West Africa, whereas Swahili is spoken thousands of miles away from there, in East Africa. Though The Official Kwanzaa Web Site has described Swahili as a “Pan-African” tongue and “the most widely spoken African language,” it is in fact a Bantu tongue that includes many words absorbed from Arabic, Persian, and Indian languages—and is spoken by only about 7% of Africa’s population. It is likely that Karenga chose Swahili as the language of Kwanzaa because it was the trendy tongue that the Black Power movement of the 1960s was promoting as an alternative to the language of white oppressors.

Karenga also created a black, green, and red flag of Kwanzaa, which, according to The Kwanzaa Information Center (KIC), “has become a symbol of devotion for African people inAmerica to establish an independent African nation on the North American Continent.” The color red, notes KIC, represents blood: “We lost our land through blood; and we cannot gain it except through blood. We must redeem our lives through the blood. Without the shedding of blood there can be no redemption of this race.”

To further promote extreme race-consciousness among African Americans, Karenga wrote the Kwanzaa pledge, which reads: “We pledge allegiance to the red, black, and green, our flag, the symbol of our eternal struggle, and to the land we must obtain; one nation of black people, with one God of us all, totally united in the struggle, for black love, black freedom, and black self-determination.”

Along with Kwanzaa’s very evident racialism, a palpable degree of anti-Americanism also sits at its heart—as Karenga made plain when he told a Washington Post interviewer in 1978: “People think it’s African, but it’s not. I came up with Kwanzaa because black people in this country wouldn’t celebrate it if they knew it was American. Also, I put it around Christmas because I knew that’s when a lot of bloods [a ’60s slang term for black people] would be partying.”

Deadly Conflict Between Karenga’s “United Slaves” & the Black Panthers

In 1969, a major conflict arose between the Black Panthers and Karenga’s organization, United Slaves, over the question of which group would control the new Afro-American Studies Center at UCLA. Karenga and his adherents backed one candidate, while the Panthers supported another. As tensions escalated, members of both groups took to carrying guns on campus—a situation that the university administration was afraid to deal with, and thus ignored. The Black Student Union, however, set up a coalition to try and bring peace between the Panthers and the United Slaves. On January 17, 1969, about 150 students gathered in a UCLA lunchroom to discuss the situation. Two Panthers—John Jerome Huggins and Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, both of whom had been admitted to the university as part of a federal program that sent high-school dropouts to college—spent a good part of the meeting launching verbal attacks against Karenga. This did not sit well with Karenga’s followers, many of whom had adopted the look of their leader—pseudo-African clothing and a shaved head. After the meeting, Huggins and Carter were met in the hallway by George and Larry Joseph Stiner, two brothers who were members of United Slaves. The Stiners pulled pistols and shot the two Panthers dead.

Members of the Panthers and the United Slaves subsequently carried out a series of additional shootings, which resulted in at least two more Panther deaths.

The Sevenfold Path of Blackness

In the aftermath of 1969 incident at UCLA, Karenga continued to build and strengthen his United Slaves organization, whose members strictly followed the rules that were laid out in The Quotable Karenga. This book demanded that Karenga’s disciples follow “the sevenfold path of blackness,” which required them to “think black, talk black, act black, create black, buy black, vote black, and live black.”

Paranoia, Brutal Torture, & Imprisonment

In the late 1960s, Karenga and his United Slaves were investigated by the FBI’s COINTELPRO operation—which was established to counteract the influence of subversive groups—and they were placed on a watch list of dangerous, revolutionary organizations.

During this period, Karenga was becoming increasingly paranoid and began to fear that some of his followers were trying to have him killed. On May 9, 1970, Karenga and two trusted allies, Louis Smith and Luz Maria Tamayo, initiated a brutal torture session against a pair of female United Slaves members, Deborah Jones and Gail Davis, who were suspected of disloyalty. The following passage from the Los Angeles Times describes what happened:

“The victims said they were living at Karenga’s home when Karenga accused them of trying to kill him by placing ‘crystals’ in his food and water and in various areas of his house. When they denied it, allegedly they were beaten with an electrical cord and a hot soldering iron was put in Miss Davis’ mouth and against her face. Police were told that one of Miss Jones’ toes was placed in a small vise which then allegedly was tightened by one of the defendants. The following day Karenga allegedly told the women that ‘Vietnamese torture is nothing compared to what I know.’ Miss Tamayo reportedly put detergent in their mouths, Smith turned a water hose full force on their faces, and Karenga, holding a gun, threatened to shoot both of them.”

The women also said that they had been “were hit on the[ir] heads with toasters” and beaten with a karate baton. These, as well as all the previously described acts of torture, were inflicted after the women had been forced to remove all of their clothes.

In a trial the following year, Karenga was convicted on two counts of felonious assault and one count of false imprisonment. On September 17, 1971, he was sentenced to serve one to ten years in prison. According to a transcript of Karenga’s sentencing hearing, Judge Arthur L. Alarcon read the following from a psychiatrist’s report:

“Since his [Karenga’s] admission here he has been isolated and has been exhibiting bizarre behavior, such as staring at the wall, talking to imaginary persons, claiming that he was attacked by dive-bombers and that his attorney was in the next cell…. During part of the interview he would look around as if reacting to hallucination and when the examiner walked away for a moment he [Karenga] began a conversation with a blanket located on his bed, stating that there was someone there and implying indirectly that the ‘someone’ was a woman imprisoned with him for some offense. This man now presents a picture which can be considered both paranoid and schizophrenic with hallucinations and elusions, inappropriate affect, disorganization, and impaired contact with the environment.”

The Disbanding of United Slaves

During Karenga’s subsequent incarceration in a California State prison, United Slaves fell into disarray and eventually disbanded in 1974.

Parole, the Return of United Slaves, & Karenga’s Conversion to Traditional Marxism

When Karenga was paroled in 1975, he re-established the United Slaves organization under a new structure. He also dropped his cultural nationalist views and converted to traditional Marxism (which focused on class struggle).

Karenga’s Doctoral Degrees

In 1976, Karenga earned a Ph.D. in political science from United States International University (now known as Alliant International University).

In 1994 Karenga earned a second Ph.D., in social ethics, from the University of Southern California.

Chairman of Black Studies Department at Cal State

In 1979, Karenga was hired to chair the Black Studies Department at California State University at Long Beach.

Speaker at Socialist Scholars Conferences

In 1990 and 1997, Karenga was a featured speaker at the Socialist Scholars Conference, an annual event sponsored by the City University of New York’s chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America.

Karenga’s Connection to Louis Farrakhan’s Million Man March

In 1995, Karenga sat on the organizing committee that authored the Mission Statement for Louis Farrakhan‘s Million Man March. Some key excerpts from that statement:

“Central to our practice of responsibility is holding responsible those in power who have oppressed and wronged us through various challenges. At the core of the practice of speaking truth to power is the moral challenge to it to be responsible, to cease its abuse, exploitation and oppression, and to observe its basic role as a structure instituted to secure human rights, not to violate them or assist in their violation. And where it has violated its trust, it must be compelled to change.

“Historically, the U.S. government has participated in one of the greatest holocausts of human history, the Holocaust of African Enslavement…. Moreover, even after the Holocaust, racist suppression continued, destroying lives, communities and possibilities…. We thus call on the government of the United States to atone for the historical and current wrongs it has committed against African people and other people of color. Especially, do we call on the government of this country to address the morally compelling issue of the Holocaust of African Enslavement. To do this, the government must: publicly admit its role and the role of the country in the Holocaust; publicly apologize for it; publicly recognize its moral meaning to us and humanity through establishing institutions and educational processes which preserve memory of it, teach the lessons and horror of its history and stress the dangers and destructiveness of denying human dignity and human freedom; pay reparations; and discontinue any and all practices which continue its effects or threaten its repetition.

“We call on the government to also atone for its role in criminalizing a whole people, for its policies of destroying, discrediting, disrupting and otherwise neutralizing Black leadership, for spending more money on imprisonment than education, and on weapons of war than social development; for dismantling regulations that restrained corporations in their degradation of the environment and failing to check a deadly environmental racism that encourages placement of toxic waste in communities of color. And of course, we call for a halt to all of this.

“Furthermore, we call on the government to stop undoing hard won gains such as affirmative action, voting rights and districting favorable to maximum Black political participation; to provide universal, full and affordable health care; to provide and support programs for affordable housing; to pass the Conyers Reparations Bill; to repeal the Omnibus Crime Bill; to halt disinvestment in social development and stop penalizing the urban and welfare poor and using them as scapegoats; to adopt an economic bill of rights including a plan to rebuild the wasting cities; to craft and institute policies to preserve and protect the environment; and to halt the privatization of public wealth, space and responsibility.

“In addition, we call on the government of the U.S. to stop blaming people of color for problems created by ineffective government and corporate greed and irresponsibility; to honor the treaties signed with Native Peoples of the U.S., and to respect their just claims and interests; to increase and expand efforts to eliminate race, class and gender discrimination, and to stop pandering to white fears and white supremacy hatreds and illusions and help create a new vision of human and societal possibilities. We also are compelled to call on the government of this country to craft a sensible and moral foreign policy that provides for equal treatment of African, Caribbean and other Third World refugees and countries; that forgives foreign debt to former colonies; that fosters a just and equitable peace and recognizes the right of self-determination of peoples in the Middle East, in the Caribbean and around the world; that rejects embargoes which penalizes whole peoples; that supports the just and rightful claims and interests of Native Peoples, and that supports all Third World countries in their efforts to achieve and maintain democracy and sustainable economic and social development. Finally, we call on the government and the country to recognize and respond positively to the fact that U.S. society is not a finished white product, but an unfinished and ongoing multicultural project and that each people has both the right and responsibility to speak their own special cultural truth and to make their own unique contribution to how this society is reconceived and reconstructed.

“We begin our challenge to corporations by rejecting the widespread notion among them, that corporations have no social responsibility except to maximize profit within the rules of an open and competitive market, through cutting costs, maximizing benefits and constantly increasing technological efficiency. Our position is that no human conduct is immune from the demands of moral responsibility or exempt from moral assessment. The weight of corporations in modern life is overwhelming and their commitment to maximizing profit and technological efficiency can and often do lead to tremendous social costs such as deteriorating and dangerous working conditions, massive layoffs, harmful products projected as beneficial, environmental degradation, deindustrialization, corporate relocation, and disinvestment in social structures and development.

“We thus call on corporations to practice a corporate responsibility that requires and encourages efforts to minimize and eventually eliminate harmful consequences which persons, communities and the environment sustain as a result of productive and consumptive practices . . . and to respect the dignity and interest of the worker in this country and abroad, to maintain safe and adequate working conditions for workers, provide adequate benefits, prohibit and penalize racial and gender discrimination, halt displacement and dislocation of workers, encourage organization and meaningful participation in decision-making by workers, and halt disinvestment in the social structure, deindustrialization and corporate relocation.

“Moreover, we call on corporations to reinvest profits back into the communities from which it extracts profits, to increase support for Black charities, contribute more to Black education in public schools and traditional Black universities and colleges, and to Black education in predominantly white colleges and universities; to open facilities to the community for cultural and recreational use and to contribute to the building of community institutions and other projects to reinvest in the social structure and development of the Black community.

“In further consideration of profit made from Black consumers, we call on corporate America to provide expanded investment opportunities for Black people; engage in partnership with Black businesses and businesspersons; increase employment of Black managers and general employees; conduct massive job training among Blacks for work in the 21st century; and aid in the development of programs to halt and reverse urban decay. Finally, we call on corporations to show appropriate care and responsibility for the environment; to minimize and halt pollution, deforestation and depletion of natural resources, and the destruction of plants, animals, birds, fish, reptiles and insects and their natural habitats; and to rebuild wasted and damaged areas and expand the number, size and kinds of areas preserved.”

Condemning an Alleged “Spate of Black Church Burnings”

In the summer of 1996, Karenga wrote an article denouncing what he called an “18-month-long spate of Black church burnings” that allegedly had occurred across the United States. He maintained that the only way to address the root cause of these “unspeakable acts” of “horror and revulsion,” “racism,” and “terrorism,” would be to initiate “a thoroughgoing change in relations of power, wealth and status” in America’s “racially hierarchical society.” Some additional excerpts from Karenga’s piece:

- “In spite of the tendency, and for some the need, to deny the racist aspect of the burnings, this recognition is central to understanding them. The burnings then are first of all acts of racism, as surely as the burning of a synagogue would be considered an anti-Jewish act. This is evidenced not only in the fact that virtually all the churches burned are Black and virtually all those arrested in these cases are white …, but also in the reality of a political culture which is significantly defined by its history of racial domination. In fact, the burning of African churches has a long genealogy in U.S. history.”

- “[I]n the context of a racially punitive culture in which whites are consistently taught to identify, condemn and despise Africans and other people of color as a central, if not the fundamental, source of their social and personal problems, one must rationally expect racially motivated acts against them.”

- “The burnings also are acts of terrorism directed toward creating a generalized and palpable sense of communal vulnerability. The terror of arson seeks to shock and shatter confidence in the central place of communal sanctuary, to shake and undermine the spiritual ground on which the community of believers stand. The intention here is to call into question and even annul the very concept of the Black church as a sanctuary, a place of refuge, security and protection and to create a communal sense of apprehension and bewilderment.”

- “Another way of understanding these burnings is to recognize that they are also acts of historical erasure, attempts to disrupt historical continuity and memory, and to interrupt the historical rhythm of communal life…. [T]he Black church is a place of records, a priceless archive of documents, objects, symbols and memory. Given this, to burn this sacred and meaningful place is to erase history and create a special sense of horror, outrage, and loss.”

Contrary to Karenga’s rhetoric, however, it was eventually learned that in fact the incidence of black church fires had increased only slightly, and temporarily, above their historically low levels. Moreover, on a per capita basis, black church fires continued to be significantly less common than white church fires.[1] By the end of 1998, just three of the more than seventy black church fires investigated by the Justice Department could be tied to racial motives. The National Church Arson Task Force likewise found few racial links.[2] It turned out, in fact, that a number of the arsonists responsible for the infamous black church fires were themselves African Americans.[3]

Falsely Accusing the CIA of Pushing Guns & Drugs in Black Communities

In 1996 Karenga wrote about “the recent revelations of the CIA’s pushing drugs and guns in the Black community,” and he called on the federal government “to apologize publicly to the African American community for this immoral, illegal and deadly project.” Further, Karenga demanded that the government change its “unjust and racist” sentencing policy, under which offenses involving crack cocaine (a drug most often used by poor blacks) were penalized more harshly than those involving powder cocaine (whose users were typically affluent whites).

Ultimately, Karenga’s claims regarding CIA malfeasance were thoroughly discredited by compelling evidence. His allegations of racism in the criminal-justice system were equally specious. The Congressional Record shows that in 1986, when the strict, federal anti-crack legislation was first being debated, the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC)—deeply concerned about the degree to which crack was decimating black communities across the United States—strongly supported the legislation and actually pressed for even harsher penalties. Moreover, the vast majority of cocaine arrests in the U.S. were made at the state—not the federal—level, where sentencing disparities between cases involving crack and powder cocaine generally had never even existed.[4]

Guest Speaker at Black Consciousness Conferences

Notwithstanding the history of acrimony between United Slaves and the Black Panthers, Karenga spoke at the 17th annual Black Consciousness Conference in November 1996, an event that featured Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale. Karenga would also be a featured guest at subsequent Black Consciousness Conferences in 1999, 2007, and 2012.

Lauding Communist Cuba’s “Heroic & Historic Struggle” Against U.S. Oppression

In 1998, Karenga and United Slaves issued a statement in support of “the Cuban people in their heroic and historic struggle to defend their right of self-determination and to break out of the unjust and immoral economic boycott by the U.S. government.” Added the statement: “[W]e respect the Cuban people for their international service in the interest of liberation, education and health for African people and other peoples around the world. And we also respect them for their ability to achieve so much with so little, in the areas of education, health care and productivity under the most stringent conditions. They offer us a model of the inherent strength, resourcefulness and dignity of a people who will not be broken or defeated.”

Eulogizing Khalid Abdul Muhammad

In February 2001, Karenga delivered a eulogy at the funeral service of New Black Panther Party leader Khalid Abdul Muhammad, praising the infamous racist and anti-Semite for his commitment to black supremacy.

Supporting Reparations for Slavery

In June 2001, Karenga wrote a piece advocating in favor of reparations payments to compensate modern-day African Americans for the “horrendous injury” that the “holocaust” of slavery and its legacy had inflicted on blacks of every generation since. “Compensation,” said Karenga, “can never be simply money payoffs either individually or collectively…. [C]ompensation itself is a multidimensional demand and option and may involve not only money, but land, free health care, housing, free education from grade school through college, etc.”

Citing American Transgressions as the Root Causes of 9/11

Six days after al Qaeda‘s September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks against the United States, Karenga wrote an article explaining that those mass murders were expressions of justifiable Muslim rage over objectionable American policies:

“… [I]t is not the material goods some of us have that they [Muslims] hate the U.S. for, but for attempts to impose the materialism of a consumerist society on them, to turn them into homogenized consumers of a McWorld system. And perhaps it is not that they are against freedom and justice and related values, but against the U.S.-imposed interpretation of this. Perhaps, they resent the arrogance of imposition and the inequities imposed by a globalism that grinds them underfoot and denies them a right of self-determination and security …

“It was an extreme act of anger, hatred and violence [that] seems under girded by a sense of abuse, oppression and state terrorism for years and decades against poor, less powerful, darker and religiously different people and the asymmetry of suffering these have inflicted. If these people [the perpetrators] were from the Middle East, then, the examples of the U.S. role in Palestine, Iraq and Lebanon stand out. But also in other parts of the world, the Contras in Nicaragua, the CIA in Guatemala and Chile, and the brutal intervention in Vietnam all speak to a U.S. role that provokes the most severe criticism, anger, resentment and hatred….

“Surely, we can and must condemn what they [the 9/11 hijackers] did, but it is also useful to imagine why they did it from their own perspective and to consider whether others feel similarly, even if they refuse to use such means to make their point. If we did, we might discover that from their perspective and those of people who will not commit such acts but are emphatic with their aims that they did it to: (1) avenge years of state terrorism, mass murder, selective assassination, collective punishment and other forms of oppression by the U.S. and its allies; (2) to demonstrate vulnerability of the U.S. at its crucial centers of power, i.e., financial—Manhattan, military—the Pentagon, and political—Washington, D.C.; (3) to cause the rulers of the country to fear, to be uncertain and to reverse the role of hunter and hunted; (4) to insist on being heard and considered in human, political and military terms; (5) to demonstrate a capacity to strike regardless of the superior strength and technology of the U.S.; and (6) to dramatize and underline in a highly visible way the asymmetry of suffering between the U.S. and the oppressed in the world….

“[W]e must defend without hesitation or equivocation the rights and equal treatment of Arabs, Muslims, Southeast Asians and others who are racially profiled and abused and attacked by the government or private citizens….

“[W]e must challenge the U.S. to review and reconstruct its international policy, especially in the Middle East, so that it is just and equitable. This will be perhaps the most difficult struggle, not simply because of our uncritical commitment to the U.S.’ major ally in the region [Israel], but also because of its shared demonization of their opponent and thus the refusal to address their [those opponents’] legitimate claims and their undeserved and asymmetrical suffering.”

Describing the War on Terror as an American “Imperial Offensive”

Karenga was an outspoken critic of the George W. Bush administration’s War on Terror, which he characterized as an exercise in “self-aggrandizement” by the U.S., and as “part of a post-9/11 imperial offensive which carries with it racist and colonial conversations and commitments of ‘crusades’ to protect ‘the civilized world’ against ‘dark and evil nations’ in ‘dark corners of the world.’”

Karenga’s Books

Karenga is the author of a number of books, most notably Introduction to Black Studies—originally published in 1981, with subsequent editions printed in 1993, 2002, and 2010—which became the most widely used introductory text in collegiate Black Studies curricula. He also authored Kwanzaa: Origins, Concepts, Practice (1977); Selections from the Husia: Sacred Wisdom from Ancient Egypt (1984); Kemet and the African Worldview: Research, Rescue and Restoration (1986, with Jacob Carruthers); The Book of Coming Forth by Day: The Ethics of the Declarations of Innocence (1990); Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture (1997); Odu Ifa: The Ethical Teachings (1999); Maat: The Moral Ideal in Ancient Egypt (2003); Kawaida Theory: An African Communitarian Philosophy (2004); and Kawaida and Questions of Life and Struggle: African American, Pan-African, and Global Issues (2008).

Karenga’s Awards

Over the course of his career as a professor and activist, Karenga has received numerous awards, including the “National Leadership Award for Outstanding Scholarly Achievements in Black Studies” from the National Council for Black Studies, and the “Pioneer Award” issued jointly by the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition and Citizenship Education Fund.

Karenga’s Career as a Teacher/Professor

Over the course of his career in academia and social activism, Karenga has held the following positions:

- 1966-1967: Instructor of Black History at the Venice Adult School, Los Angeles

- 1966-1969: Lecturer/Consultant on “Ideology and Community Organization” at the Center for Social Action, UCLA

- 1966-1969: Lecturer/Consultant on “Minority and Urban Problems” at the Institute for Training and Program Development, Los Angeles

- 1968: Lecturer/Consultant on “Social Action,” “Community Organization,” and “Black/Brown Cooperative Projects” at the Social Action Training Center, Los Angeles

- 1968: Lecturer/Consultant on “Social Action” and “Community Organization” at the Urban Training Center, Chicago

- 1968: Lecturer/Consultant on “Leadership and Community Organization” at the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organizers (IFCO) and the Ohio Organizing Project at the University of Dayton

- 1968: Lecturer/Consultant on “The Dynamics and Dimensions of Black Power” at Brandies University’s Leimburg Center for the Study of Violence

- 1976: Lecturer at Seminar on “The Political Economy of the Black Community,” held at UC San Diego

- 1976: Teacher of Record, “Multicultural Approaches in Education,” San Diego State University Extension

- 1976-1977: Teacher of Swahili at Grossmont College

- 1977: Black Studies Instructor at San Diego City College

- 1977: Visiting Professor, “Seminar on Black Politics of the Sixties” at Stanford University

- 1977-1978: Adjunct Professor, “Social Change,” United States International University, San Diego

- 1977-1979: Associate Professor of Pan-African Studies at California State University, Los Angeles

- 1979-1982: Professor of Black Studies at California State University, Long Beach

- 1980: Distinguished Visiting Scholar, Black Studies, at the University of Nebraska, Omaha

- 1982-1983: Associate Professor of Afro-American Studies at California State University, Dominguez Hills

- 1983-1984: Visiting Professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Washington, Seattle

- 1984: Associate Professor of Afro-American Studies at San Diego State University

- 1984-1989: Professor of Black Studies and Ethnic Studies at UC Riverside

- 1989-Present: Professor in the Department of Black Studies at California State University, Long Beach (Karenga has also served as chairman of the Cal State University President’s Task Force on Multicultural Education and Campus Diversity.)

Footnotes:

- “Hiding Behind the Smoke,” Washington Post (June 18, 1996), p. A 13.

- Deroy Murdock, “Everyday America’s Racial Harmony,” The American Enterprise (November/December 1998), p. 25.

- “Hiding Behind the Smoke,” Washington Post (June 18, 1996), p. A 13. “Indiana Man Admits to 50 Church Arsons,” The New York Times (February 24, 1999), p. A 18.

- Richard Cohen, “Class, Not Race,” Washington Post (November 14, 1995).

Additional Resources:

Happy Kwanzaa

By Paul Mulshine

December 26, 2002