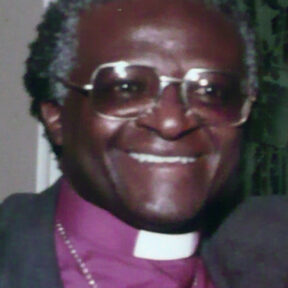

Desmond Tutu

: Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: Ellin Beltz rephotographed a framed original owned by Sally Tanner.Overview

* Former Archbishop of Cape Town, South Africa

* Winner of the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize for his work against South African apartheid

* Condemned America’s military response to the 9/11 attacks

* Said the 9/11 attacks were caused by the “poverty, hunger, and disease” plaguing the Third World, which he blamed, by implication, on the U.S.

* Asserted that “Israel is like Hitler and apartheid”

* Advocated divestment from Israel

* Died on December 26, 2021

Desmond Tutu was born in October 1931 in the Transvaal region of northern South Africa. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in theology from King’s College in London (1962-1966). He then returned to South Africa, where from 1967 to 1972 he lectured to draw attention to the plight of blacks living under that country’s apartheid system.

In 1967 Tutu became chaplain at the University of Fort Hare, South Africa, a hotbed of anti-apartheid dissent. From 1970 to 1972 he lectured at the National University of Lesotho, calling for a worldwide boycott against South African products as a means of pressuring the government to discontinue its racially discriminatory practices.

In 1972 Tutu relocated to the United Kingdom, where he was appointed vice-director of the Theological Education Fund of the World Council of Churches. Three years later he migrated to South Africa and was appointed Anglican Dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg.

By the mid-1970s, Tutu was actively engaged in a nascent anti-apartheid boycott movement. He served as Bishop of Lesotho from 1976 until 1978, when he became Secretary-General of the South African Council of Churches.

In the early 1980s Tutu derided U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s “constructive engagement” policy which advocated “friendly persuasion” against apartheid. Instead, Tutu continued to push for a full-blown economic boycott against his country.

In 1984 Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize for his anti-apartheid activism. By 1985, his divestment campaign had succeeded because the U.S and the United Kingdom agreed to terminate their investments in South Africa.

Seeking to permanently break the back of apartheid by riding this wave of British and American support, Tutu organized peaceful demonstrations that drew some 30,000 people onto the streets of Cape Town. A few months later Nelson Mandela was freed from prison, and the fabric of the apartheid system began to come apart.

In 1985 Tutu was appointed Bishop of Johannesburg. In September 1986 he became Archbishop of Cape Town, a position that rendered him the leader of South Africa’s Anglican Church.

After the fall of apartheid in the early 1990s, Tutu chaired a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) investigating apartheid-era crimes. In 1996 he stepped down from his post as Archbishop of Cape Town and was given the honorary title “Emeritus Archbishop of Cape Town.”

In the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Tutu said that the collateral, unintended killing of Afghan civilians during America’s retaliatory military campaign (against the Taliban and al-Qaeda) was the moral equivalent of the 9/11 mass murders in New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C. “Might is not right,” said Tutu. “If it is utterly reprehensible that innocent civilians were targeted in New York and Washington, how could we possibly say it doesn’t apply elsewhere in the world?” In January 2003 Tutu lamented how “sad” it was “to see a powerful country [the U.S.] use its power frequently unilaterally” to bully the rest of the world.

Tutu characterized America’s war on terrorism as an exercise in “vengeance” rather than justice. Underlying this assertion was the premise that the Islamic enemy that had struck the U.S. on 9/11 was not animated by premeditated aggression, but was itself responding to America’s original provocations.

While acknowledging that al-Qaeda was a terrorist organization, Tutu maintained that many of its operatives and supporters were “not lunatic fringe [but rather] are quite intelligent.” Americans, he expanded, needed to ask themselves why such people “should be willing to pilot a plane and go to their deaths” to strike a blow against the U.S.

To that question, Tutu himself provided a ready answer. The 9/11 attacks, he explained, were caused by the “poverty, hunger, and disease” plaguing the Third World, which he blamed, by implication, on the United States. Tutu said that if an observer from outer space were to survey the international scene on earth, such a creature would recoil in horror at the manner in which the wealthy U.S. spent so much money on its war-making capabilities and so little on humanitarian causes. “A minute fraction of these defense budgets would ensure that God’s children everywhere would have clean water, enough to eat, a decent home, a proper education, and accessible and affordable health care,” said Tutu.

Addressing worshippers at Boston’s Episcopal Church of St. Paul in February 2002, Tutu asserted that it was wrong to categorically depict America’s foes around the world as “evil.” “We’re giving up on a fellow human being when we demonize a fellow human being,” he said. Exhorting his listeners to remember that Saddam Hussein, Osama bin Laden, and all so-called terrorists are children of God, he stated that “the Christian God we worship gives up on no one.” Complaining, in a similar spirit, that America was too quick to condemn people, he said in a 1999 speech that “some of the greatest saints in the Christian firmament were notorious sinners,” and he wondered aloud whether such biblical icons as Mary Magdalene and St. Francis “would have survived indictment” in the United States.

Tutu revered Winnie Mandela, South Africa’s so-called “Mother of the Nation.” Prominent in the Soviet-sponsored African National Congress (ANC), which was closely aligned with the South African Communist Party, Mrs. Mandela used her notorious bodyguards in a protracted reign of terror, torture, and murder during the 1980s. The ANC committed innumerable atrocities in the name of liberation, prompting a 1988 Pentagon Report to list it as one of the world’s “more notorious terrorist groups.”

Many ANC victims were physically pummeled and brutalized to death – some of them on the direct orders of Mrs. Mandela. Among the ANC’s preferred methods of torturing suspected political opponents was “necklacing” – a practice where automobile tires were tied around the necks of victims, filled with gasoline and lit on fire. It is estimated that some 1,000 people were set ablaze in this manner, with nearly 600 of them dying. “With tires and matches we will liberate this country,” said the celebrated “Mother of the Nation.”

Notwithstanding Mrs. Mandela’s role in such atrocities (which Tutu did, in fact, criticize on numerous occasions), the Archbishop said the following to her during South Africa’s Truth & Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings:

“I speak to you as someone who loves you very, very deeply, who loves your family very deeply. There are people who want to embrace you. There are many who want to do so. I beg you, I beg you, I beg you, please. I have not made any particular finding about what happened. You are a great person, and you don’t know how your greatness would be enhanced if you were to say, sorry, things went wrong; forgive me. I beg you.”

At that point, Mrs. Mandela reluctantly admitted that “it is true things went horribly wrong,” and she issued apologies to the families of two of her murdered victims.

Tutu’s stance on the Arab-Israeli conflict was decidedly anti-Israel. In April 2002 he joined some 300 people for a pro-Palestinian rally in Boston, a demonstration that urged an end to U.S. military aid to Israel and an immediate pullout of Israeli forces from the West Bank. Later that day, Tutu spoke at a conference on violence in the Middle East at Boston’s Old South Church. “What is not so understandable [and] not justified,” he said, “is what [Israel] did to another people to guarantee its existence.” Claiming that his visits to Israel reminded him of the manner in which blacks were once treated in South Africa, he said, “I have seen the humiliation of the Palestinians at checkpoints and roadblocks, suffering like us when young white police officers prevented us from moving about.”

Tutu further complained that Americans are too often afraid to criticize Israel. “The Jewish lobby is powerful, very powerful,” he said. “[Y]ou know as well as I do that, somehow, the Israeli government is placed on a pedestal [in the U.S.], and to criticize it is to be immediately dubbed anti-Semitic…. I am not even anti-white, despite the madness of that group.”

Asserting that “Israel is like Hitler and apartheid,” Tutu urged his Boston listeners to oppose Israeli “injustices” as fervently as they once had opposed Nazism and South Africa’s system of racial separation. “We live in a moral universe,” said Tutu. “The apartheid government was very powerful, but today it no longer exists. Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, Pinochet, Milosevic, and Idi Amin were all powerful, but in the end they bit the dust.” Notably, Tutu had no words of condemnation for PLO leader Yasser Arafat — the man responsible for the murder of more Jews than anyone since Hitler.

As a tangible expression of his view that Israeli policies stand in the way of peace in the Middle East, Tutu endorsed the Israeli Divestment Campaign. He said:

“The end of apartheid stands as one of the crowning accomplishments of the past century, but we would not have succeeded without the help of international pressure – in particular the divestment movement of the 1980s…. [A] similar movement has taken shape, this time aiming at an end to the Israeli occupation. Divestment from apartheid South Africa was fought by ordinary people at the grassroots. Faith-based leaders informed their followers, union members pressured their companies’ stockholders, and consumers questioned their store owners. Students played an especially important role by compelling universities to change their portfolios. Eventually, institutions pulled the financial plug, and the South African government thought twice about its policies. Similar moral and financial pressures on Israel are [now] being mustered one person at a time.”

Tutu issued no call for divestment from any other Middle Eastern nation — though the political oppression, human rights abuses, and barbaric atrocities characterizing life throughout much of that region have long dwarfed anything that the Palestinians have ever suffered in Israel, which Tutu dubbed America’s “client state.” This double standard is reminiscent of the double standard that characterized the anti-apartheid crusade in the 1980s. In those days, there was nary a whisper about possible divestment from any of the myriad African nations where campaigns of ethnic cleansing, wholesale torture and mutilation, and the genocide of millions were a way of life.

Tutu was a member of the so-called “Elders” — an independent group, founded by Nelson Mandela, of global leaders “who work together for peace and human rights.” In January 2014, Tutu and several fellow Elders traveled together to Iran, where they paid tribute to the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Tutu was an honorary member of the Phelps Stokes board of trustees.

Tutu died on December 26, 2021 in Cape Town, South Africa.

Much of this profile is adapted from the article, “Nobel Hypocrite,” authored by John Perazzo and published by FrontPageMag.com on January 23, 2003.