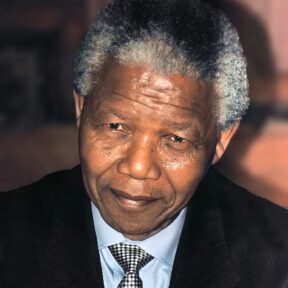

Nelson Mandela

: Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: Unknown authorOverview

* Former President of South Africa

* Member of the African National Congress

* Established the African National Congress Youth League

* Created the militant group Umkhonto we Sizwe

* Was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for a series of bombings against government buildings and homes of government officials

* Longtime friend of Yasser Arafat, Fidel Castro, and Moamar Qaddafi

* Died on December 5, 2013

Nelson Mandela was born in Qunu, a village in eastern South Africa, in 1918. His father was a councilor to the Acting Paramount Chief of South Africa’s Thembuland region; after his father died, the young Mandela became the Chief’s ward. Bypassing a career in the Chief’s administration, Mandela determined instead to become a lawyer. He entered the University College of Fort Hare, was suspended for leading a boycott, and eventually earned his B.A. via correspondence. He move to Johannesburg and worked as a law clerk while studying for his legal degree at the University of Witwatersrand. In 1942, he joined the African National Congress.

The African National Congress had been founded in 1912 as the South African Native National Congress; its purpose was to defend the rights of blacks against the white minority; the Act of Union, which formed South Africa in 1910, deprived most blacks of the right to vote. A few who were allowed to vote around Cape Town soon lost that right after the establishment of the apartheid regime in 1948. The Native Congress quickly became radicalized and aligned itself first with trade unionism, then with socialism. The leading South African socialist parties merged with the Communist Party in 1920s, and in 1923 the South African Native National Congress changed its name to the African National Congress to reflect its growing internationalist, Communist outlook.

In its early phase, the group focused on non-violent resistance; Mandela, his future law partner Oliver Tambo, and several other young African students in and around Witwatersrand established the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL). Mandela was one of the drafters of the group’s manifesto. The ANCYL criticized the more genteel ANC and promised to politicize and radicalize the movement. It succeeded.

After World War II, the National Party took control of the government. It took away the franchise from the few blacks who had retained it after the Union was established, and later took away the vote from the “Coloureds,” i.e., people of mixed-race descent. The government attempted the Bantustan policy, i.e., the division of South African blacks into 10 “homelands,” and required that blacks carry passes if they intended to travel outside of their homelands.

The ANC, led by Mandela’s ANCYL, adopted the Programme of Action, a statement of policy that endorsed the use of strikes, boycotts, and the somewhat more menacing “such other means as may bring about the accomplishment and realization of our aspirations.” Mandela took part in the 1952 Defiance Campaign as the ANC’s National Volunteer in Chief. For his part in the campaign, Mandela was arrested and tried under the government’s Suppression of Communism Act. He was given a suspended sentence when the judge agreed that Mandela had so far encouraged only non-violent resistance. In fact, throughout the 1950s, although his demand for Socialist reforms was strong and constant, as witnessed by the Freedom Charter of 1955, Mandela continued to adhere, publicly at least, to principals of peaceful resistance.

The year 1956 saw the apartheid government begin the Treason Trials, a round-up of 160 subversives that went on for years. Mandela stood trial in 1958; the transcript of his trial resembles a political debate rather than a court hearing. At this time, two parties, the Liberal and Progressive, were already working to dismantle the voting restrictions and economic oppression of apartheid. In the midst of the ongoing trials and the political maneuverings, disaster struck in the form of the Sharpeville Massacre.

Sharpeville has long been considered the key event in the isolation of South Africa from the rest of the world. The tangled events that led to the massacre have been difficult to unravel. The Pan-Africanist Congress, an offshoot of the ANC, organized a protest at the Sharpeville Township police station. A crowd variously estimated at 5,000 to 7,000 descended on the station, intent on burning their reference books, (identification booklets that the apartheid government required blacks to carry at all times), and offering themselves for arrest in an act of civil disobedience. At some point, the police in the compound opened fire, killing 69 protestors and wounding 180. Reports at the time indicated that the protestors may have initiated the violent confrontation by throwing stones at the police. That was the story that became commonplace in the Western press and led to the severing of South Africa from the British Commonwealth, outraged protests from all over the world, and the decision of Mandela to endorse violence as a means to achieve his ends.

The reporting of the Sharpeville Massacre turned world opinion solidly against South Africa. It withdrew from the British Commonwealth and became the Republic of South Africa, adopting a more restrictive constitution, in part in defiance of international pressure, in part because of the increasingly militant posture of the South African blacks. The ANC and the PAC were outlawed. Sharpeville also marked a definite turning point for Mandela and other members of the ANC, who now opted for the use of force to accomplish their political agenda. An offshoot militant wing, the Umkhonto we Sizwe (UWS), the “Spear of the Nation,” was created by Mandela and others to bring the apartheid government down by use of sabotage. Mandela went underground and eventually left the country without permission, training in terrorist camps in Algeria and addressing the Pan-African Freedom Movement conference in Addis Ababa in January 1962. His speech was a masterpiece of one-sided distortions, as he condemned the South African government for atrocities like Sharpeville or Bulhoek (a 1921 incident in which government officers, attempting to enforce an eviction warrant on squatters, were attacked by a mob of religious fanatics and returned fire, killing 163; Mandela refers to them as ‘unarmed’, an adjective not supported by accounts at the time), invariably oversimplifying the complex background of each incident. He spoke approvingly of bombings in Fort Hare, Durban, and Johannesburg, and claimed that he was sending ANC members for guerrilla training.

Mandela returned to South Africa in 1962 and while in custody, was arrested and tried in the Rivonia trials. Rivonia was the headquarters of a group of saboteurs accused of blowing up not only government buildings but also the homes of government officials. Mandela did not deny that he was a member of the UWS and that it was engaged in sabotage, but claimed that the UWS did not engage in bombings of private homes. He also denied the possibility of finding real justice in a “White Man’s Court”.

Sometimes lost in the reports of the trial was a document that South African police found when they raided the UWS headquarters, the plans for Operation Maribuye, which detailed the targets that the UWS intended to hit and listed the strategic and tactical considerations that the group should consider. It is, in effect, a plan for war, and contrary to the rhetoric of the ANC and Mandela, both at the trial and in subsequent years, the UWS saboteurs had already claimed lives as well as buildings for their victims.

Mandela was convicted and sentenced to life in prison; he was incarcerated at Robben Island, a maximum-security prison near Cape Town; he was later transferred to Pollsmoor Prison in Cape Town, then to Victor Verster Prison, from which he was eventually released in 1990. Mandela repeatedly declined offers of early release from prison in exchange for his support of the government’s Bantustan plans.

During his imprisonment, the ANC unleashed a reign of terror and torture that has been well-documented. In 1997, during the TRC hearings, the ANC leadership admitted to at least 550 actions carried out by its UWS wing, with another 100 incidents that “may or may not” have been carried out by members acting on their own. The terrorist attacks included the infamous “necklacings,” in which attackers put a gasoline-soaked tire around the victim’s neck and then set it afire (a tactic often ascribed to Mandela’s wife, Winnie, and her followers), bombings of government and military installations, and the establishment of secret “re-education” camps in northern Angola, Tanzania, and Uganda where the ANC would torture those reluctant to go along with its program of violence. In addition to warring with the apartheid government, the ANC often battled other black groups, particularly the Zulu-led Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). The government, for its part, employed equally violent means of quelling black resistance. The death totals for the period from 1985-1994 reached 23,000, according to the TRC.

In 1990, as the government of Frederik DeKlerk moved to end apartheid, the ANC was legalized and Mandela was released from prison. In part, DeKlerk was motivated by the collapse of the Soviet Union, which had made no secret of its desire to control South Africa’s vast mineral wealth and keep it out of Western hands. With the USSR gone, the Communist threat vanished. For his part, Mandela, in a 1991 speech to a joint meeting of the ANC and IFP, urged black Africans to abandon terrorist tactics and to use peaceful methods to end apartheid. He and DeKlerk shared the 1993 Nobel Prize for their efforts.

In 1994, South Africa held its first multi-party, multi-racial elections. The ANC took 68 percent of the available seats and has retained power ever since. The elections were marked by serious scandal, which was largely underreported or ignored by the press. The ANC intimidated people entering and leaving the voting booths; IFP candidates were left off ballots; children of ANC party members were allowed to vote; and some polls never even opened. Nonetheless, the international observers declared the elections “free and fair.” Mandela was inaugurated president in that same year. Since then, the largely unsuccessful administrations of Mandela and his hand-picked successor, Thabo Mbeki, have plunged what was once an orderly and somewhat prosperous country into an abyss of crime and poverty.

Mandela’s ANC and its economic policies have been largely subservient to the Communist controlled South African trade unions (COSATU); the South African union workers have low productivity rates and, compared to China and other parts of Asia, vastly higher wages. Government overregulation has stifled small business development, and investment by foreign countries has also been discouraged by the lawlessness of South Africa. More economic difficulty looms as black businesses attempt to expropriate the wealth and property of white-owned enterprises.

Crime has been rampant and largely underreported by the press. In the KwaZulu-Natal provincial elections of 1996, for example, the South African press admitted to underreporting the number of people killed in election violence in order to stop the freefall of South Africa’s currency, the Rand. Government prosecutors have complained of being hampered by party considerations in their pursuit of political murderers. The rate of rape against women, both white and black, has been extraordinary. The rape of children, sometimes in exchange for cash payments to the parents, has also been on the rise. Crimes against white farmers have been on the increase, with at least 6,000 attacks leading to 1,600 murders and innumerable rapes and assaults reported since the end of apartheid. Overall estimates of those killed in all violent crimes in the country since 1991 total 230,000.

Incidents of HIV infection have been rising steadily, fueled in part by the declaration of Mandela’s successor, President Mbeki, that AIDS is not linked to the HIV virus. The country’s hospitals have, for the most part, deteriorated, and diseases long thought to be cured have returned. Much of the road system, sewer systems, and the electrical grid have fallen into decay. Corruption is rife at all levels of government. The South African army, once one of the best in the world, has disintegrated into loosely organized bands of thugs. Mandela, Mbeki, and the ANC have turned South Africa – once the most prosperous power in southern Africa into a genuineThird World country.

In recent years, Mandela – a longtime friend of Arafat, Castro and Qaddafi, has been sharply critical of U.S. support for Israel, no doubt animated by the fact that South Africa was, during apartheid, one of Israel’s strongest supporters, and that support was reciprocated. He has criticized the U.S. and Great Britain for the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and has accused President Bush of lacking vision in dealing with the Middle East.

He passed away on Thursday, December 5, 2013 in Johannesburg, South Africa.