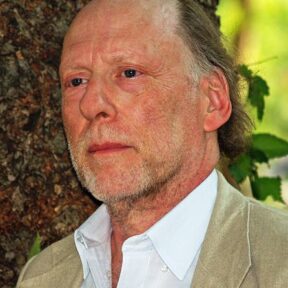

Todd Gitlin

Overview

* Former professor at the Columbia School of Journalism

* Anti-war activist, author of book on the Sixties

* Served as president of Students for a Democratic Society in the 1960s

* Died on February 5, 2022

Born in 1943, Todd Gitlin was a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism. He is also an occasional contributor to The Nation.

After graduating from the Bronx High School of Science, Gitlin attended Harvard University, the University of Michigan, and UC Berkeley. He went on to teach at Berkeley for many years.

Professor Gitlin was the author of The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage — a standard apologia for the 1960s, firmly committed to the view that this was a progressive rather than a destructive generation. As a chronicler of the events of that decade, Gitlin largely refused to acknowledge the actual crimes committed by radicals like the Black Panther Party activists who were responsible for a series of robberies, arsons and murders, preferring instead to view their thuggery as actions that were provoked by a repressive society.

Gitlin was a President of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which was the largest student organization of the New Left in the early 1960s.

A strong supporter of the post-9/11 antiwar movement, Gitlin stated that the very “essence” of American policy in the War on Terror was “monumental arrogance.” Not only was arrogance “the hallmark of [President] Bush’s foreign policy,” Gitlin wrote, but “it is his foreign policy.”

Gitlin participated in the infamous March 2003 Columbia University “teach-in,” where fellow professor Nicholas De Genova expressed his fervent wish that American soldiers might be slaughtered en masse in “a million Mogadishus,” — a sentiment that Gitlin strongly dissented from, but not enough to wish America victory in its war in Iraq.

Writing on the website of Mother Jones four months prior to the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom, Gitlin expressed his desire to build a “more substantial antiwar movement.” He also expressed his disappointment that the pro-Saddam orientation of the antiwar movement could only stand in the way of that task. He characterized the movement as reflective of “the Old Left at its worst,” and lamented that with leadership by the likes of Ramsey Clark and the Maoist radical C. Clark Kissinger, “the antiwar movement is doomed.” In short, Gitlin implied that the goals of the movement to stop any planned invasion of Iraq were worthy, and that only its current leadership was problematic.

After 9/11, Professor Gitlin wrote an article critical of leftists who opposed the war against the Taliban in Afghanistan, and he even unfurled an American flag and hung it from his apartment window for a few weeks. But he soon re-furled it because, “leaving the flag up was too easily misunderstood as a triumphalist cliché. It didn’t express my patriotic sentiment, which was turning toward political opposition…”

This opposition quickly turned into contemptuous condemnation of his country’s efforts to liberate Iraq. Gitlin wrote: “By the time George W. Bush declared war without end against an ‘axis of evil’ that no other nation on earth was willing to recognize as such — indeed, against whomever the president might determine we were at war against,…and [he] declared further the unproblematic virtue of pre-emptive attacks, and made it clear that the United States regarded itself as a one-nation tribunal of ‘regime change,’ I felt again the old estrangement, the old shame and anger at being attached to a nation — my nation — ruled by runaway bullies, indifferent to principle, their lives manifesting supreme loyalty to private (though government slathered) interests, quick to lecture dissenters about the merits of patriotism.”

In a 2003 article titled “Varieties of Patriotism,” Gitlin reflected upon the decades he had spent harboring the belief that America was ultimately unworthy of his respect or allegiance. “For a large bloc of Americans my age and younger,” he wrote, “too young to remember World War II — the generation for whom ‘the war’ meant Vietnam and possibly always would, to the end of our days — the case against patriotism was not an abstraction. There was a powerful experience underlying it: as powerful an eruption of our feelings as the experience of patriotism is supposed to be for patriots. Indeed, it could be said that in the course of our political history we experienced a very odd turn about: The most powerful public emotion in our lives was rejecting patriotism.”

Coming of age in the era of the Vietnam War, then, was the perceived cause of what Gitlin described, on another occasion, as his persistent sense of “estrangement,” “shame,” and “anger at being attached to a nation.”

Between 2007 and 2010, Gitlin was a member of JournoList, an online listserve of media professionals that functioned essentially as a secret society of bloggers and reporters who coordinated the way they presented certain stories so as to advance leftist political candidates and agendas.

Gitlin was a signatory to September 2015 letter that a pair of coalitions called “Partners for Progressive Israel” and “Scholars for Israel and Palestine” sent to every member of Congress, urging the lawmakers to approve the nuclear agreement that the Obama administration and the governments of five other nations were negotiating with Iran. That accord, said Gitlin and his fellow signers, would force Iran to: “forswea[r] further development of nuclear weapons, commi[t] to significant reductions in its current nuclear capabilities, and agre[e] to intrusive inspections” that “will greatly reduce the chances of war with Iran and will enhance the security of Israel.” (For details about what the Iran nuclear deal actually stated, click here.) Another noteworthy signatory of the letter to Congress was Eric Alterman.

Gitlin died on February 5, 2022 in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

Parts of this profile are adapted from the article “The Anti-War Movement: Then and Now,” written by Ronald Radosh and published by FrontPageMagazine.com on November 6, 2002.