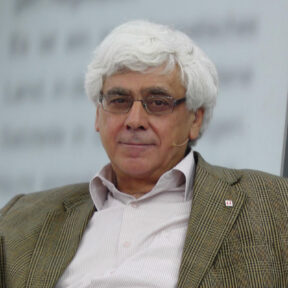

Sari Nusseibeh

: Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: Blaues SofaOverview

* Professor of Islamic Philosophy and the president of Al Quds University in Jerusalem

* Helped organize the first Palestinian Intifada, 1987-1993

* Seeks the ultimate destruction of Israel

* Supports Palestinian suicide bombings, but discourages them for tactical purposes — so as to not lose other nations’ support for his cause

Born in Damascus, Syria in February 1949, Sari Nusseibeh studied politics, philosophy, and economics at Oxford University, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in 1971. After receiving a doctorate in Islamic philosophy from Harvard in 1978, he relocated to the West Bank and worked as an assistant professor of philosophy at Birzeit University until 1990. During that same period, Nusseibeh also taught classes in Islamic philosophy to Jewish students at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

In the early to mid-1980s, Nusseibeh became active in political and labor-related affairs. He served three terms as president of the teachers’ union at Birzeit, and he co-founded the Federation of Employees in the Education Sector for the entire West Bank.

In 1987 Nusseibeh became the first prominent Palestinian to hold talks with a senior Israeli Likud politician, Moshe Amirav¯a move that drew fierce criticism from Palestinian activists. On September 21, 1987, he was badly beaten while leaving the Bir Zeit University campus¯probably by Fatah elements who were angered by his outreach to the Likud.

From 1987-1993, Nusseibeh was a leading organizer of the first Palestinian Intifada. He also helped draft the Palestinians’ 1988 declaration of independence, which depicted the creation of Israel as a “historical injustice” that had led to “organized [Israeli] terror,” the “occupation of Palestine and parts of other Arab territories,” the “dispossession and expulsion [of Palestinians] from their ancestral homes,” and the “destruction of [the Palestinians’] national life.”

In the 1989 trial of four Palestinians accused of belonging to the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising, the underground group that coordinated the Intifada, Nusseibeh was named by Israel as an unindicted co-conspirator. He was further believed to have channeled¯from the PLO-in-exile to the Palestinian Territories¯funds that were then used to finance terrorist operations against Israel. Nusseibeh denied the allegations, and no formal charges were brought.

In June 1989, Israel closed down Nusseibeh’s Holy Land Press Service, which was furnishing foreign correspondents and diplomats with news about the Intifada, for two years¯on suspicion that it had been helping to bankroll the uprising. Nusseibeh’s English-language weekly newsletter, Monday Report¯which likewise provided analysis of the Intifada‘s major events¯was banned as well.

During the 1991 Gulf War, Nusseibeh worked with the Israeli organization Peace Now to condemn the collateral killing of civilians. He was arrested and placed under administrative detention less than two weeks after the start of that conflict, on suspicion that he was an Iraqi agent.

In 1995 Nusseibeh became a professor of Islamic philosophy at Al Quds University in Jerusalem; that same year, he was named the university’s president. He continues to hold both posts to this day.

Over the course of his academic career, Nusseibeh has cultivated a reputation among Western leftists as a pacifist dedicated to improving Palestinian-Israeli relations. National Public Radio, for example, has called him “a voice of moderation.” This view of Nusseibeh derives, in part, from his ostensibly pragmatic recommendation that the Palestinians, as a measure by which to forge a lasting peace with Israel, should abandon their quest to achieve a “right-of-return” to their 1948 homes: “It is not full justice,” he explained in 2001, “but it is practical justice, this is what is possible.”

But whereas Nusseibeh articulates themes of peace and tolerance to English-speaking audiences, he routinely endorses hatred and jihad when addressing Arabic listeners. In a December 2001 appearance on Al-Jazeera television, for instance, he advocated both the Palestinian right-of-return and Yasser Arafat‘s strategy of working to bring about Israel’s destruction in “stages“¯through a sequence of small, pragmatic steps disguised as attempts to foster peace.

Nusseibeh’s Western admirers, however, turn a blind eye to such inconsistencies in his message. In June 2002, Nusseibeh further impressed these supporters when he led a group of Palestinian activists in signing a statement¯published in the West Bank-based daily newspaper Al Ayyam¯calling for “a cessation of the bombings that target Israeli civilians inside Israel.” But on a Qatari television broadcast that aired just a few days after the publication of the Al Ayam statement, Nusseibeh participated in a panel discussion with a Hamas leader and the mother of a Hamas terrorist who had recently murdered seven Israelis; he expressed “all respect” for Islamic jihadists and their parents, who he said would surely be rewarded in “Paradise.”

In October 2001 Nusseibeh was appointed by Yasser Arafat as a PLO representative in Jerusalem, making him the highest Palestinian official in the city. He retained this position for 14 months.

In a November 2007 Arabic-language interview, Nusseibeh made it clear that “[n]o Jew in the world, now or in the future … will have the right to return, to live, or to demand to live in Hebron, in East Jerusalem, or anywhere in the Palestinian state.”

For additional information on Sari Nusseibeh, click here.