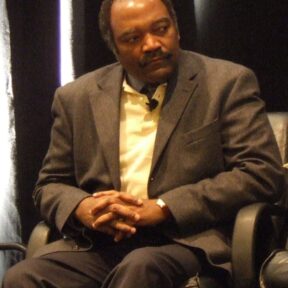

Mark Lloyd

: Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: joebeoneOverview

* Disciple of Saul Alinsky’s tactics for revolutionary social change

* Served as a consultant to the Bill Clinton White House

* Was a consultant to the MacArthur Foundation, George Soros’s Open Society Institute, & the Smithsonian Institution

* Was a senior fellow at John Podesta’s Center for American Progress

* Was appointed as Diversity Chief of the FCC in 2009

* Was VP of strategic initiatives at the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights

* Seeks to use “diversity” and “localism” as pretexts for shifting the political balance of talk-radio programming leftward

* Suggests that private broadcasters should pay an annual licensing fee that should be redistributed to public stations

* Opposes virtually all private ownership of media

* Greatly admired Venezuela’s late Marxist President, Hugo Chavez

Mark Lloyd earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan and a Juris Doctorate from the Georgetown University Law Center. He went on to work as a communications attorney at the firm Dow, Lohnes & Albertson, and he served as general counsel for the Benton Foundation. He also has been a producer and reporter for various radio and television networks, including NBC and CNN. From 2002 to 2004, he was a Martin Luther King Jr. Visiting Scholar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. During various periods of his career, he has served as a consultant to the Bill Clinton White House, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, George Soros’s Open Society Institute, and the Smithsonian Institution. He was also a senior fellow at John Podesta’s Center for American Progress.

In July 2009 Lloyd was appointed to be Diversity Chief of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). At the time of that appointment, Lloyd was an affiliate professor of public policy at Georgetown University. He was also vice president of strategic initiatives at the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR), a legislative advocacy group describing itself as “the nation’s oldest and largest civil rights coalition … representing persons of color, women, children, labor unions, individuals with disabilities, older Americans, major religious groups, gays and lesbians …”

LCCR condemns the American criminal-justice system as a thoroughly racist institution; supports the quest for socialized medicine by such organizations as Health Care for America Now; contends that racism permeates the housing market and the money-lending industry; views the U.S. as a sexist nation that discriminates against women, particularly in terms of workplace compensation; supports the League of United Latin American Citizens’ vision of immigration reform, where illegal aliens would be permitted, en masse, to pursue a pathway to citizenship; favors voting rights for ex-felons; and contends that the existence of poverty in America is due to “the gates of economic opportunity” being “mostly closed to minorities, women, and others by both governmental and private action.” Lloyd himself embraces each of these positions.

In June 2007 Lloyd co-authored a report titled “The Structural Imbalance of Talk Radio,” commissioned jointly by the Center for American Progress and the Free Press. This publication states that because “91 percent of the total weekday talk radio programming is conservative, and 9 percent is progressive,” the stations and networks that air such shows are failing to abide by Section 315 of the Communications Act of 1934, which “requires commercial broadcasters to operate in the public interest and to afford reasonable opportunity for the discussion of conflicting views of issues of public importance.”

Lloyd dismisses outright what he calls the “two primary explanations typically put forth to explain the disparities between [the respective amounts of] conservative and progressive talk radio programming.” Says Lloyd:

“In the first argument, the explosion of conservative talk radio is attributed to the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine by the [FCC] in 1987. The Fairness Doctrine was a regulation … that required broadcasters to devote airtime to important and controversial issues and to provide contrasting views on these issues in some form. From this perspective, the repeal of the doctrine in the late 1980’s allowed station owners to broadcast more opinionated, ideological, and one-sided radio hosts without having to balance them with competing views.”

This development, the theory goes, gave rise to the growth of the talk radio format spearheaded by such conservative personalities as Rush Limbaugh, G. Gordon Liddy, and Sean Hannity. Leftist/liberal radio has not produced anyone of similar stature.

But Lloyd says “the Fairness Doctrine was never, by itself, an effective tool to ensure the fair discussion of important issues.” He explains:

“The Fairness Doctrine was most effective as part of a regulatory structure that limited license terms to three years, subjected broadcasters to license challenges through comparative hearings, required notice to the local community that licenses were going to expire, and empowered the local community through a process of interviewing a variety of local leaders.”

To address each of these issues, Lloyd recommends that the FCC take the following steps “to ensure local needs are being met”:

- “Require radio broadcast licensees to regularly show that they are operating on behalf of the public interest and provide public documentation … of how they are meeting these obligations.”

- “Provide a license to radio broadcasters for a term no longer than three years.” In other words, every three years radio stations would be evaluated for their compliance with the mandate that they serve “the public interest.” (Section 307 of the 1996 Telecommunications Act extended the length of broadcast-license terms to eight years.)

- “Demand that the radio broadcast licensee announce when its license is about to expire and demonstrate how the public can participate in the process to determine whether the license should be extended.” (Such a modus operandi would provide ample opportunity for activist groups like ACORN to stage high-profile, public demonstrations against radio stations whose political content they find objectionable.)

Unless the foregoing steps are taken, says Lloyd: “Simply reinstating the Fairness Doctrine will do little to address the gap between conservative and progressive talk.”

Lloyd likewise dismisses the other most commonly cited theory as to why conservative talk radio is so much more popular than liberal/left formats — the contention that “station owners are merely providing the programming that the market forces demand.” Says Lloyd:

“Although talk radio audiences tend to be more male, middle-aged, and conservative, research by Pew indicates that this audience is not monolithic … It is difficult to argue that the existing audience for talk radio is only interested in hearing one side of public debates, given the diversity of the existing and potential audience.”

In Lloyd’s calculus, a more accurate assessment is that “the imbalance in talk radio programming today” is a result of “the elimination of clear public interest requirements such as local public affairs programming, and the relaxation of ownership rules, including the requirement of local participation in management.”

Specifically, Lloyd contends that when the Telecommunications Act of 1996 “removed the national limit on the number of radio stations that one company could own,” it triggered the development of a “wave” of “conglomerates” consisting of “several hundred stations apiece.” Says Lloyd:

“The economics of radio station ownership changed in this period as a result of consolidation. Large, non-local owners aired syndicated programming on a wider scale across their national holdings. Advertising on local stations was marketed and sold by national firms, undermining the ability of local owners to compete. Many sold their stations. The number of locally-owned, minority-owned, and female-owned stations was constrained—and the very different programming decisions these owners make were less visible in the market.”

“[T]he market solution,” Lloyd concludes, “has clearly failed to meet audience demand.”

Lloyd further points out that “stations owned by racial or ethnic minorities are statistically less likely to air conservative hosts or shows, and [are] more likely to air progressive hosts or shows.” “Minority and female owners,” he adds, “who tend to be more local, are more responsive to the needs of their local communities and are therefore less likely to air the conservative hosts because this type of programming is so far out of step with their local audiences.” (The notion that broadcasters should tailor their programming to the preferences and the perceived needs of their local audiences is called “localism.”) And finally, says Lloyd: “Stations controlled by owners who run just a single station [are] statistically less likely to air conservative talk and more likely to air progressive hosts or shows.”

“Ultimately,” Lloyd maintains, “these results suggest that increasing ownership diversity, both in terms of the race/ethnicity and gender of owners, as well as the number of independent local owners, will lead to more diverse programming, more choices for listeners, and more owners who are responsive to their local communities and serve the public interest.”

In other words, “diversity” and “localism” go hand-in-hand, and both can be used as pretexts for shifting the political balance of radio programming leftward.

In the final analysis, Lloyd believes the federal government should intervene to limit the presence of conservatives in the broadcast media:

- “National radio ownership by any one entity should not exceed 5 percent of the total number of AM and FM broadcast stations.”

- “In terms of local ownership, no one entity should control more than 10 percent of the total commercial radio stations in a given market.”

Lloyd justifies these limits under the rubric of “localism,” a concept that President Barack Obama himself has cited as a key consideration for the issuance of broadcast licenses. On September 20, 2007, Obama submitted a written statement supporting localism at an FCC hearing held at the Chicago headquarters of Jesse Jackson‘s Operation Push.

Under localism’s dictates, the degree to which radio stations conform their programming to government-mandated ideological guidelines will determine whether or not they are able to successfully renew their broadcast licenses every three years. “All radio broadcast licensees should be required to use a standardized form to provide information on how the station serves the public interest in a variety of areas,” says Lloyd. “The form should be made public on a quarterly basis and maintained in the station’s public inspection file …”

In his 2006 book, Prologue to a Farce: Communications and Democracy in America, Lloyd suggests that private broadcasters should pay an annual licensing fee in an amount equivalent to their total yearly operating costs. That money, in turn, should be redistributed to public broadcasting stations (which supposedly are more in tune with their audiences’ needs), thereby ensuring that the operating budgets of such stations will be just as large as those of their privately owned counterparts. (Broadcasters who cannot afford to pay the fee would lose their broadcast licenses, which would then be sold to minority broadcasters.)

In short, stations that are successful and profitable would be required to turn over an enormous portion of their earnings to competitors that are failures in the marketplace. Writes Lloyd:

“Federal and regional broadcast operations and local stations should be funded at levels commensurate with or above those spending levels at which commercial operations are funded. This funding should come from license fees charged to commercial broadcasters.”

In Prologue to a Farce, Lloyd argues that the U.S. communications environment has become unfairly dominated by corporate interests. “Citizen access to popular information has been undermined by bad political decisions,” he writes. “These decisions date back to the Jacksonian Democrats’ refusal to allow the Post Office to continue to operate the telegraph service.”

Throughout history, Lloyd laments, “The most powerful communications tool was deliberately placed in the hands of one faction in our republic: commercial industry.” He identifies government as the “only” institution that can adequately manage public communications systems and bring to fruition “our collective responsibility” of “provid[ing] for the equal capability of citizens to participate effectively in democratic deliberation.”

Seton Motley of the Media Research Center points to the following as “the most disturbing thing” about Lloyd:

“He is fundamentally opposed to virtually any private ownership of media. He is fundamentally opposed — he faults — the original sin in communications, in his opinion, is when Jefferson — President Jefferson relinquished control, the Post Office control of the telegraph. When they relinquished control to a private entity, that was the original sin of communications because that turned over communications vehicles to the private sector outside of the scope of government control.”

Warning of the potential dangers posed by conservative domination of talk radio in the U.S., Lloyd draws a parallel between that state of affairs and the one-sided control of radio stations that existed in the African country of Rwanda in 1994. Beginning that April, roving gangs of bloodthirsty ethnic Hutus massacred approximately 800,000 Rwandan Tutsis in three months. The seeds of that genocide, Lloyd contends, were sown as a result of Hutu control (and exploitation) of the airwaves, which the Hutus used to disseminate calls for the mass murder of their hated ethnic rivals:

“State radio in Rwanda was taken over by one tribe — one group — and they began to put out propaganda so that the Tutsis were targeted. And what resulted…was essentially a mass genocide in Rwanda. The State, or this particular tribe which controlled the radio, very purposefully moved to ensure they could ‘do things.’ Uh, their media, their social change.”

Lloyd views governmental control over the airwaves in the U.S. as a potentially potent “means of social change” because of radio’s capacity, if harnessed properly, to give all Americans “a political voice” and access to “information that they can trust.” By contrast, he views conservative talk radio largely as a source of misinformation. To combat that misinformation, he advocates the abrogation of free speech, as evidenced by this excerpt from Prologue to a Farce:

“It should be clear by now that my focus here is not freedom of speech or the press…. This freedom is all too often an exaggeration…. At the very least, blind references to freedom of speech or the press serve as a distraction from the critical examination of other communications policies.”

At a May 2005 event titled “Conference on Media Reform: Racial Justice,” Lloyd advanced the idea that affirmative action programs were needed to dramatically shift the racial balance of workers in the media industry:

“This… there’s nothing more difficult than this. Because we have really, truly good white people in important positions. And the fact of the matter is that there are a limited number of those positions. And unless we are conscious of the need to have more people of color, gays, other people in those positions we will not change the problem. We’re in a position where you have to say who is going to step down so someone else can have power.

“There are few things I think more frightening in the American mind than dark skinned black men. Here I am.”

Lloyd’s strategy to greatly diminish, if not to eliminate altogether, the influence of conservative talk radio, is based heavily on the tactics of Saul Alinsky, the late community organizer who, in the middle decades of the 20th century, painstakingly laid out a detailed blueprint for revolutionary social change. Citing Alinsky repeatedly as his primary inspiration, Lloyd outlines nine “lessons” he considers vital to the potential political success of the Left:

- “Organizing people must be a priority. In order to counter effectively the power of major corporations, we understood that we had to be able to demonstrate the support of hundreds of thousands of people. As Alinksy wrote: ‘Change comes from power, and power comes from organization. In order to act, people must get together.’”

- “Understand where people stand on your issue…. As Alinksy wrote, ‘if people feel they don’t have the power to change a bad situation, then they do not think about it.’”

- “Connect with groups that have already organized the community … groups that had large constituencies and articulated our message by identifying how our goals fit their core interests.”

- “The strategy must have an inside and an outside game. For media reform, this means we needed to embrace the necessity of operating both in and outside Washington [D.C.].”

- “Don’t wait for events to unfold on their own. Pressure, pressure, pressure … not at the government, but through the government at our true opposition – the broadcasters. Alinsky again: ‘The major premise for tactics is the development of operations that will maintain constant pressure upon the opposition.’” [This point echoes Lloyd’s 2009 assertion that: “We must build a confrontational movement to reclaim our democracy, a movement committed to active and sustained protest against the present order.”]

- “Communications is a priority. Again drawing from Alinksy, we understood that ‘one can lack any of the qualities of an organizer – with one exception – and still be effective. That exception is the art of communication’ … so the public and your opposition see you and your issues the way you want to be seen.”

- “Research is key. We took not only message and public opinion research seriously, we took seriously our obligation to research the activity of our opposition.”

- “Establish a broad base of funding and never stop raising money. Alinksy is right that people are a source of power, but without adequate funds organizing people effectively cannot be accomplished.”

- “Find allies in power. If civil rights leaders such as King had the Kennedys and Johnson, and the anti-Bork campaign had Ted Kennedy, our main ally was [FCC Chairman] Bill Kennard.” “We looked to successful political campaigns and organizers as a guide,” adds Lloyd, “especially the civil rights movement, Saul Alinsky, and the campaign to prevent the Supreme Court nomination of the ultra-conservative jurist Robert Bork. From those sources, we drew inspiration and guidance.”

Lloyd is a great admirer of Venezuela’s Communist President, Hugo Chavez. At a June 10, 2008 National Conference for Media Reform in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Lloyd said:

“In Venezuela, with Chavez, is really an incredible revolution — a democratic revolution. To begin to put in place things that are going to have an impact on the people of Venezuela. The property owners and the folks who then controlled the media in Venezuela rebelled — worked, frankly, with folks here in the U.S. government — worked to oust him. But he came back with another revolution, and then Chavez began to take very seriously the media in his country.”

Chavez, it should be noted, is a steadfast opponent of free-speech rights for his political adversaries. In a March 1, 2009 televised address to his nation, he said that “if it weren’t for the attack, the lies, manipulation and the exaggeration” of the private media networks, the Venezuelan government would enjoy the support of at least four-fifths of the population. Thus he ordered his governors and mayors to draw up a “map of the media war” to determine which media were “in the hands of the oligarchy.” During Chavez’s 2009 campaign for a constitutional amendment to remove term limits for elected officials, a statistical analysis found that more than 93 percent of the Venezuelan state news channel’s coverage of the proposed amendment was favorable.