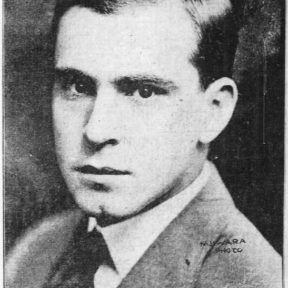

Roger Baldwin

: Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: Takuma Kajiwara / Original Source of Photo: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/16935956/the_st_louis_star_and_times/Overview

* Founder of the American Civil Liberties Union

* Enthusiastic proponent of Communism

* Died in 1981

Born in Wellesley, Massachusetts on January 21, 1884, Roger Nash Baldwin was educated at Harvard College, where he earned a BA in 1904 and an MA the following year. Baldwin then moved to St. Louis, where he taught sociology at Washington University from 1906-09; served as chief probation officer of the city’s Juvenile Court (1907–10); and was secretary of the reformist Civic League of St. Louis (1910–17). Also during his time in St. Louis, Baldwin developed a friendship with the anarchist Emma Goldman and became involved in radical political and social movements. Baldwin would later describe his attendance at a 1909 lecture by Goldman as ”a turning point in my intellectual life.” ”What I heard in that crowded working-class hall from a woman who spoke with passion and intelligence,” he said, ”was a challenge to society I had never heard before. Here was a vision of the end of poverty and injustice by free association of those who worked, by the abolition of privilege and by the organized power of the exploited.”

At the approach of World War I, Baldwin co-founded the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation, which steadfastly opposed the use of warfare in the settlement of international disputes. Among Baldwin’s colleagues in this endeavor were the perennial Socialist presidential candidate Norman Thomas, the pacifist/Marxist A. J. Muste, and The Nation editor Oswald Garrison Villard.

When the U.S. entered the War in 1917, Baldwin helped establish the American Union Against Militarism (AUAM), again with the aim of promoting a pacifist, internationalist agenda. Soon thereafter, the AUAM created a Civil Liberties Bureau and appointed Baldwin as its leader. This Bureau subsequently broke away from AUAM, renamed itself the National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB), and expanded its scope to include also the defense of freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

Baldwin was a socialist who counseled subterfuge as the preferable means of promoting his political agendas in the United States. In a private 1917 letter (to the journalist/activist Louis Lochner, who was affiliated with a radical organization), Baldwin wrote: “Do steer away from making it look like a Socialist enterprise. We want to look like patriots in everything we do. We want to get a lot of flags, talk a good deal about the Constitution and what our forefathers wanted to make of this country, and to show that we are really the folks that really stand for the spirit of our institutions.”

In 1918 Baldwin was sentenced to a year in jail for refusing to register for the military draft. In a speech to the court, he said: ”The compelling motive for refusing to comply with the draft act is my uncompromising opposition to the principle of conscription of life by the state for any purpose whatever, in time of war or peace.” After his release from incarceration nine months later, Baldwin spent a year as a wandering blue-collar laborer, riding free in empty freight cars as he roamed the Midwest. In 1919 he joined the Industrial Workers of the World.

When Baldwin married the attorney/reformer Madeleine Z. Doty in 1919, he read to his bride the following statement, emphasizing the undesirability of values that seem to be compatible with capitalism — most notably, “possession”:

“To us who passionately cherish the vision of a free human society, the present institution of marriage among us is a grim mockery of essential freedom…. We deny without reservation the moral right of state or church to bind by force of law a relationship that cannot be maintained by the power of love alone…. The highest relationship between a man and a woman is that which welcomes and understands each other’s loves. Without a sense of possession, there can be no exclusions, no jealousies. The creative life demands many friendships, many loves shared together openly, honestly, and joyously…”

When the NCLB was renamed the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 1920, Baldwin became its executive director and went on to hold that post for the next 30 years.

In addition to his work with the ACLU, Baldwin in the early 1920s was the leading official of the Garland Fund, a major financier of Communist Party enterprises.

Though Baldwin said he was not a Communist Party member, he visited Joseph Stalin’s Russia in 1924 and wrote that it had become “a great laboratory of social experimentation of incalculable value to the development of the world.” Pragmatically viewing the “repressions in Soviet Russia” as “weapons of struggle in a transition period to socialism,” he saw such abuses as necessary avenues to a desirable end. “I accepted the fact that civil liberties were not suitable for Russia,” he once averred.

Baldwin visited the Soviet Union again in 1927, and a year later he published a book entitled Liberty Under the Soviets, which contained effusive praise for the USSR.

In the 1930s Baldwin and the ACLU became linked to the Popular Front movement, which was engendered by Stalin to strengthen the Communist Party by allowing it to make common cause with socialists and other leftist groups.

In 1934 Baldwin and his wife, Madeleine Z. Doty, divorced. Two years later, Baldwin wed yet another reformer, Evelyn Preston, who would remain his wife until her death in 1962.

In 1934 Baldwin authored a piece titled “Freedom in the USA and the USSR,” which revisited the theme of political repression as a necessary evil in the noble quest for utopia:

“The class struggle is the central conflict of the world; all others are incidental. When that power of the working class is once achieved, as it has been only in the Soviet Union, I am for maintaining it by any means whatever. Dictatorship is the obvious means in a world of enemies at home and abroad. I dislike it in principle as dangerous to its own objects. But the Soviet Union has already created liberties far greater than exist elsewhere in the world…. [There] I saw … fresh, vigorous expressions of free living by workers and peasants all over the land. And further, no champion of a socialist society could fail to see that some suppression was necessary to achieve it. It could not all be done by persuasion…. [I]f American champions of civil liberty could all think in terms of economic freedom as the goal of their labors, they too would accept ‘workers’ democracy’ as far superior to what the capitalist world offers to any but a small minority. Yes, and they would accept—regretfully, of course—the necessity of dictatorship while the job of reorganizing society on a socialist basis is being done.”

In 1935 Baldwin wrote the following in the thirtieth-anniversary-reunion edition of his Harvard University class book:

“My ‘chief aversion’ is the system of greed, private profit, privilege, and violence which makes up the control of the world today, and which has brought it the tragic crisis of unprecedented hunger and unemployment…. I am for Socialism, disarmament, and ultimately the abolishing of the state itself as an instrument of violence and compulsion. I seek social ownership of property, the abolition of the propertied class, and sole control by those who produce wealth. Communism is the goal. It all sums up into one single purpose—the abolition of dog-eat-dog under which we live, and the substitution by the most effective non-violence possible of a system of cooperative ownership and use of all wealth.”[1]

Baldwin again wrote the foregoing statement in a December 31, 1938 affidavit for inclusion in the record of the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Baldwin altered his stance on the USSR in 1939, when the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact was signed. Angry that the Soviets had betrayed their stated principles by aligning themselves with Hitler, Baldwin in 1940 sought to have all Communists removed from the ACLU board; the Communist labor organizer, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, was among those purged from the organization.

Recognizing the threat posed by Nazi Germany, Baldwin also dropped his longtime opposition to the military draft during the Second World War.

In 1942 Baldwin helped establish the International League for the Rights of Man (later called the International League for Human Rights, or ILHR).

In 1947 General Douglas MacArthur invited Baldwin to Japan to foster the protection of civil liberties in that country, where Baldwin subsequently founded the Japan Civil Liberties Union. In 1948, American General Lucius Clay invited Baldwin to Germany and Austria for similar purposes.

Baldwin retired as executive director of the ACLU in 1950 but remained active in the organization thereafter. Indeed he kept an office in the United Nations, working as a consultant for the ILHR.

Baldwin traveled extensively after his retirement, especially to Asia, where he embraced the Communist dictator Ho Chi Minh as a member of the Vietnamese-American Friendship Association, which gave favorable publicity to the Viet Cong. Baldwin also cultivated the friendship of convicted terrorist Pedro Albizu Campos in Puerto Rico. Moreover, Baldwin was an early member of the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, which argued for unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United States.

In his later years, Baldwin, reflecting on his time as the ACLU’s executive director, said: “I don’t regret being part of the communist tactic. I knew what I was doing. I was not an innocent liberal. I wanted what the communists wanted and I traveled the United Front road to get it. Communism is good.”

President Jimmy Carter presented Baldwin with the Presidential Medal of Freedom on January 16, 1981.

In addition to his aforementioned affiliations, Baldwin also had ties to the National Conference of Social Welfare, the National Urban League, the American League for Peace and Democracy, the North American Committee for Spanish Democracy, the Inter-American Association for Democracy and Freedom, the Friends of the Soviet Union, and Americans for Intellectual Freedom.

Baldwin died of heart failure seven months later, at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, New Jersey, on August 26, 1981.

Footnotes:

- “Baldwin, ‘From the Harvard Classbook,’” (June 1935, vol. 763). From Roger Nash Baldwin and the American Civil Liberties Union [New York: Columbia University Press, 2000], pp. 228-229.

Additional Resources:

What Does the “A” Really Stand For?

By Matthew Vadum

August 12, 2009

BOOKS:

Roger Nash Baldwin and the American Civil Liberties Union

By Robert Cottrell

2000

The Politics of the American Civil Liberties Union

By William A. Donohue

1985

The ACLU vs. America: Exposing the Agenda to Redefine Moral Values

By Alan Sears & Craig Osten

2005

Further Reading: “Roger Nash Baldwin” (Britannica.com); “Roger Baldwin, 97, Is Dead” (NY Times, 8-27-1981).