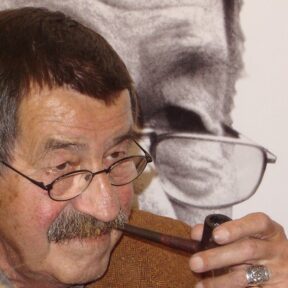

Gunter Grass

Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: Florian KOverview

* Nobel laureate and novelist

* Germany’s leading public intellectual

* Longtime left-wing political activist

* Died on April 13, 2015 in Lübeck, Germany

Born in 1927 in the city of Danzig (today the Polish city Gdañsk), Günter Grass was a Nobel Prize-winning author and one of Germany’s leading public intellectuals; he was the country’s most famous novelist.

Famous for his left-wing political activism as well as his celebrated books, Grass has gone from one political extreme to the other. In his early teens, Grass was a member of the Hitler Youth, Nazi Germany’s paramilitary youth training program. At the age of 16, Grass, by his own account under the sway of Nazi indoctrination, was drafted as an artillery soldier into the Nazi army, the Wehrmacht. Upon the end of the war, Grass was briefly interned at an American-run prisoner of war camp in Bavaria.

In 1955, Grass joined “Group 47,” an informal collective of West German writers uniformly left-wing in their politics. The group’s dual mission was to promote the writings of its members and to push them toward greater involvement in German political affairs. Grass became the group’s most successful member when he published The Tin Drum in 1959. Widely regarded as his best work and a catalyst for his 1999 Nobel Prize for literature, it helped launch his literary and political celebrity.

With his commercial success, Grass assumed a more active role in politics. In the 1960s, he emerged as an outspoken supporter and occasional speechwriter for the left-of-center Social Democratic Party (SPD) and its candidate, and later the German Chancellor, Willy Brandt. (Grass only formally joined the SPD after it had been ousted by the center-right Christian Democratic Union in 1982.) Grass resigned the SPD in 1992 in protest of its support for the removal of a provision in the German constitution guaranteeing political asylum. At the time, Grass denounced politicians who opposed blanket asylum as closeted Nazis, who wear “skins in the government” but “think the same way as the kids who shave their heads and carry swastikas…”

Also in the 1990s, Grass strongly opposed German unification, on the grounds that Germans had forfeited any right to nationhood because of the atrocities of Nazi Germany. “The crime of genocide, summed up in the image of Auschwitz, inexcusable from whatever angle you view it, weighs on the conscience of the unified [German] state,” he insisted. Despite his penchant for linking modern Germany with the atrocities of the Nazi era, and his repeated calls for an honest account of German history, Grass himself admitted only in July of 2006 that he served in the Waffen SS in the final months of World War II.

Throughout his career, Grass has been a constant critic of the United States. Dismissing American criticism of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the novelist claimed that “the United States was disqualified from making moral judgments about anything” because of its alleged abuse of human rights in the past. In the 1980s, Grass took part in demonstrations against the deployment of U.S. missiles in Germany to defend the country against the Soviet Union and assailed U.S. support for Poland’s anti-Soviet Solidarity trade union movement. While delivering his Nobel lecture in 1999, Grass made a point of singling out the United States for its “active support” of the “terror” in Chile in 1973, when a military coup (in fact unaided by the United States) toppled the socialist president Salvador Allende. In 2003, Grass charged the US, in fighting terrorists and their rogue-state sponsors, with creating an enemy “where none exists,” and declared that the real threat to international security issued from President Bush. “The current US president is the perfect expression of this common danger we face,” Grass wrote in London’s Guardian newspaper.

Grass’s hostility to the United States stands in stark contrast to his uncritical support for left-wing dictatorships. After being led on a tour of Nicaraguan prisons by a Sandinista operative in the 1980s, Grass pronounced the country a realized utopia where “Christ’s words are taken literally.” Grass also repeatedly traveled to Central America to heap praise on communist governments. Of Fidel Castro’s Cuba Grass said in 1993 that “Cubans were less likely to notice the absence of liberal rights” because they gained “self respect” after the revolution. Grass was also a steadfast proponent of communist East Germany and complained before its collapse in the 1990s that the end of the GDR could spell a “prohibition on dreaming” about the feasibility of socialism.

In 2012 Grass published a controversial anti-Israeli poem titled What Must Be Said (Was gesagt werden muss) in the German daily Süddeutschen Zeitung. In the poem, Grass states that “it is suspected” (but not known with certainty) that “a bomb is being built” in Iran; he opposes the sale to Israel of a German submarine “whose specialty consists of guiding all-destroying warheads to where the existence/of a single atomic bomb is unproven” (falsely implying that Israel was contemplating a nuclear first-strike against Iran); he argues that “the nuclear power of Israel endangers/the already fragile world peace.” Defaming Israel as a “perpetrator” of “recognized danger” and urging it to “renounce violence,” Grass affirms that he is no longer silent because he is “tired of the hypocrisy of the West.”

He passed away on April 13, 2015 in Lübeck, Germany