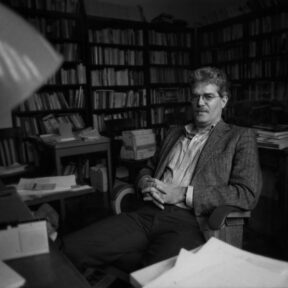

Bruce Cumings

: Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: JimiwoOverview

* America’s leading leftist historian on Korean history

* Blames mostly the U.S. for starting the Korean War

* Wrongly denied that the Soviet Union sponsored North Korea’s invasion of South Korea

* Minimized the horrors of North Korea’s famine of the 1990s

* Refuses to acknowledge that communism has been the cause of North Korea’s economic catastrophes

* Blames the U.S. for its current political tensions with North Korea

* Says that 9/11 “bears comparison to the sick individuals with some sort of grievance who have shot up schools, malls or the Capitol Building in the U.S., and who are later shown not to have taken their daily dose of thorazine”

* Says that the Bush administration overreacted to 9/11 by pouring “billions into ‘Homeland Defense’ while showing a callous disregard for civil liberties, the rights of the accused, and the views of America’s traditional allies”

Born in Rochester, New York in 1943, Bruce Cumings is the Gustavus F. and Ann M. Swift Distinguished Service Professor in History at the University of Chicago, where he has taught since 1984. Before joining the Chicago faculty, he taught at Swarthmore College and the University of Washington.

Cumings is, in the words of writer Anders Lewis, “the left’s leading scholar of Korean history.” Cumings’ research focuses on 20th-century international history, U.S.-East Asian relations, modern Korean history, and American foreign relations. He has authored numerous books, including the two-volume set, The Origins of the Korean War (1981, 1990); War and Television (1993); Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (1997); Parallax Visions: American-East Asian Relationships at the End of the Century (1998); and North Korea: Another Country (2003). He also co-authored (with Ervand Abrahamian and Moshe Ma’oz) Inventing the Axis of Evil (2004). He has been a frequent contributor to The Nation magazine and the New Left Review.

Cumings earned a B.A. in psychology from Denison University in 1965, and an M.A. from the University of Indiana in 1967. After completing his studies at Indiana, he spent several months in the Peace Corps (stationed in Seoul, South Korea) before enrolling at Columbia University, where he pursued his doctoral studies beginning in the fall 1968 semester. He recounts: “By that time, I was so disgusted with the [Vietnam] war that I was willing to take whatever consequence the draft board threw at me. But when I enrolled at Columbia … along came a student deferment. I’ve never understood why that happened. If I hadn’t gotten it, I don’t know what I would have done, but I definitely wouldn’t have gone to the military….”

At Columbia, Cumings became a member of the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars (CCAS). According to the Tibetan political activist and writer Jamyang Norbu, the CCAS was “a now discredited organization of left-wing Mao-worshipping American sinologists who subscribed unquestioningly to the belief that Mao and the Communist Party of China had not only solved the problems of China but that of humankind as well; and that Communist China should be regarded as a model not just for developing nations, but also the United States.”

Cumings received his Ph.D. from Columbia in 1975.

According to Cumings, the Korean War (1950-53) had multiple causes, “with blame enough to go around for everyone.” He places some of that blame on the Soviet Union, which was, he asserts, “unconcerned with Korea’s ancient integrity and determined to ‘build socialism’ whether Koreans wanted their kind of system or not.” But mostly he blames the “Americans who thoughtlessly divided Korea and then reestablished the colonial government machinery and the Koreans who served it.” In the final analysis, Cumings depicts the Korean War as a U.S. initiative of racist aggression that amounted to a veritable holocaust for the Korean people. The United States, he contends, had no moral justification for interfering in what he calls “a civil war, a war fought by Koreans, for Korean goals.” He cites the “significant responsibility that all Americans share for the garrison state that emerged on the ashes of our truly terrible destruction of the North half a century ago.” “I don’t have sympathy for North Korea,” Cumings has written elsewhere, “but I have empathy for them in part because my country tried to totally destroy them for three years during the Korean War and nearly came close to doing it.”

According to historian Allan Millett, Cumings’ “eagerness to cast American officials and policy in the worst possible light … often leads him to confuse chronological cause and effect and to leap to judgments that cannot be supported by the documentation he cites or ignores.”

Korea expert B.R. Myers, writing in the Atlantic Monthly, has identified a few of Cumings’ more egregious scholarly errors. For example, writes Myers: “In a book concluded in 1990 [Cumings] argued that the Korean War started as ‘a local affair,’ and that the conventional notion of a Soviet-sponsored invasion of the South was just so much Cold War paranoia.” But as Myers points out, the very next year Russian authorities began declassifying the Soviet archives, “which soon revealed that [North Korean President] Kim Il Sung had sent dozens of telegrams begging Stalin for a green light to invade, and that the two met in Moscow repeatedly to plan the event.”

“Cumings went on,” adds Myers, “to write an account [Korea’s Place in the Sun, 1997] of postwar Korea that instances the North’s ‘miracle rice,’ ‘autarkic’ economy, and prescient energy policy (an ‘unqualified success’) to refute what he calls the ‘basket-case’ view of the country. With even worse timing than its predecessor, [this book] went on sale just as the world was learning of a devastating famine wrought by [North Korean capital] Pyongyang’s misrule.”

According to Myers, Cumings’ 2003 book, North Korea: Another Country, “likens North Korea to Thomas More’s Utopia.” “At one point in [this book],” writes Myers, “we are even informed that the regime’s gulags [a prison system designed to punish real and imagined political dissidents] aren’t as bad as they’re made out to be, because [President] Kim Jong Il is thoughtful enough to lock up whole families at a time.” “The mixture of naiveté and callousness,” Myers notes, “will remind readers of the Moscow travelogues of the 1930s, but Cumings is more a hater of U.S. foreign policy than a wide-eyed supporter of totalitarianism. The book’s apparent message is that North Korea’s present condition can justify neither our last ‘police action’ on the peninsula nor any new one that may be in the offing.”

In North Korea: Another Country, Cumings approvingly quotes a writer who claimed that prior to the nation’s recent economic disasters, its typical residents had lived “an incredibly simple and hardworking life but also [had] a secure and happy existence, and the comradeship between these highly collectivized people [was] moving to behold.” While acknowledging that the totalitarian North Korean regime is anathema to individual liberty, Cumings condemns even more harshly the “U.S. support for dictators who make Kim Jong II look enlightened.” In Cumings’ view, Americans’ negative impressions of North Korea’s political system are rooted in an admixture of their own ignorance and racism. To place the horrors of the gulags in what he deems proper perspective, Cumings reminds his readers of the “longstanding, never-ending gulag full of black men in our [U.S.] prisons” — which ought to preclude Americans from “pointing a finger” of condemnation at North Korea.

Cumings steadfastly refuses to acknowledge that communism has been the cause of North Korea’s economic catastrophes of recent years — a stark contrast to the capitalist South Korean economy that has performed well (with per capita incomes approximately 20 times greater than those in the North) since the 1980s. The professor’s affinity for communism was clearly on display when, in a debate with Ronald Radosh, Cumings was asked if he thought communism was evil. He said no, and declared that many people enthusiastically embraced such a system.

In another review of North Korea: Another Country, sociology professor Paul Hollander writes: “Cumings belongs to the long line of Western academic intellectuals who are fully persuaded that the United States bears responsibility for much that is wrong with the world, including the existence of political systems and movements that are its most dedicated adversaries. Not only does he believe that the U.S. is largely responsible for the (defensive) brutality and pugnacity of North Korea, he is equally eager to acquaint the reader with the achievements of this regime — which include ‘compassionate child care’ and superior health and education benefits.”

According to Hollander, Cumings “is eager to dispel any impression of North Korean aggression against the South (which in fact culminated in its 1950 invasion); he even uses the disingenuous argument that the conflict was a civil war and that the 38th parallel is ‘not an international boundary.’ He dwells on the sufferings the U.S. inflicted during that war, and thus creates a framework for his apologetic reinterpretation of the paranoid garrison state North Korea has become. His emphasis on the inhumanities of U.S. air warfare is reminiscent of the argument that the U.S. bombing of Cambodia somehow prompted the massacres of Pol Pot. Thus a very familiar theme pervades the narrative: ‘Beleaguered’ North Korea … did some bad things, but it was due to feeling and being threatened and victimized by the U.S.”

In yet another review of North Korea: Another Country, Anders Lewis summarizes some of Cumings’ major assertions as follows: “During the Cold War, they [the North Koreans] avoided dependence on the Soviet Union, created a productive economy, and improved living standards. The society they created is impressive. North Korea’s streets are clean, its people humble, and crime is almost non-existent. Kim Il Sung, the father of North Korean communism, was a ‘a classic Robin Hood figure’ who cared deeply for his people. North Korea’s current leader, Kim Jong Il, is ‘not the playboy, womanizer, drunk, and mentally deranged fanatic Dr. Evil of our press.’ Instead he is a ‘homebody who doesn’t socialize much, doesn’t drink much, and works at home in his pajamas.’ The Dear Leader also loves to tinker with music boxes, watch James Bond movies, and play Super Mario video games….”

Adds Lewis: “In general … Cumings adopts a decidedly positive portrait of the DPRK [Democratic People’s Republic of Korea]. Consider, for example, his comments on an election he witnessed in 1987 in Pyongyang. He writes that he ‘watched the hoopla at each polling place’ and ‘was struck by the quaint simplicity of this ritual: a dubious yet effective brass band, old people bent over canes in the polling lines and accorded the greatest respect, young couples in their finest dress dancing in the chaste way I remember from square dances in the Midwest of the 1950s, and little kids fooling around while their parents waited to vote.’ While getting sappy about his boyhood, Cumings fails to consider what type of ‘election’ he had witnessed, or how much real choice North Koreans had during this ‘quaint’ affair.”

In Cumings’ calculus, America — particularly the George W. Bush administration — is largely to blame for the recent strained relations between North Korea and the United States. In December 2003, Cumings wrote:

“For more than a decade, the North Koreans have been trying to get American officials to understand that genuine give-and-take negotiations on their nuclear program could be successful, based on the terms of a ‘package deal’ that they first tabled in November 1993. The North has steadfastly said it would give up its nukes and missiles in return for a formal end to the Korean War, a termination of mutual hostility, the lifting of numerous economic and technological embargoes, diplomatic recognition, and direct or indirect compensation for giving up very expensive programs. Their willingness to do this was tested in 1994, when they froze their nuclear complex and kept it frozen under the eyes of UN inspectors for eight years.”

“In June 1994,” Cumings added, “Jimmy Carter got North Korea to agree to a complete freeze on activity at the Yongbyon complex, and a Framework Agreement was signed in October 1994. The Republican Right railed against this for the next six years, until George W. Bush brought a host of the Agreement’s critics into his Administration, and they set about dismantling it, thus fulfilling their own prophecy and initiating another dangerous confrontation with Pyongyang. The same folks who brought us the invasion of Iraq and a menu of hyped-up warnings about Saddam Hussein’s weapons have similarly exaggerated the North Korean threat: indeed, the second North Korean nuclear crisis began in October 2002, when ‘sexed-up’ intelligence was used to push Pyongyang against the wall and make bilateral negotiations impossible….”

“Diplomacy with the North,” said Cumings on another occasion, “is anathema because the Republican right won’t allow it and because the same group that brought us an illegal war with Iraq wants to overthrow Kim Jong Il.” In Cumings’ opinion, the U.S., not North Korea, should compromise on negotiations over nuclear weapons — on grounds that Pyongyang simply, and understandably, would “like to have nuclear weapons like those that the United States amasses by the thousands.”

Cumings contends that Bill Clinton was an outstanding U.S. President in comparison to his successor, George W. Bush, particularly vis a vis his dealings with Korea. “We all know Clinton’s flaws,” says Cumings, “including those of his diplomacy and warfare, but in [retrospect] his leadership shines like a beacon — as if the Enlightenment were unaccountably followed by the Dark Ages.”

According to Cumings, the 9/11 Islamist attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon can best be explained not as the logical outcome of a longstanding jihadist tradition in the Muslim world, but rather as the mindless act of a handful of deranged individuals. Says Cumings, 9/11 “bears comparison to the sick individuals with some sort of grievance who have shot up schools, malls or the Capitol Building in the U.S., and who are later shown not to have taken their daily dose of thorazine.” Muslims, he expands, “do have legitimate grievances, and one of them is the continuing mutual terror of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.”

In Cumings’ estimation, the American response to the 9/11 attacks was ill-advised and disproportional. “Any administration would have responded forcefully to the attacks of September 11,” he says, “but Bush and his allies have vastly distended the Pentagon budget …, added another zone of military containment (Central Asia), created an American West Bank the size of California in Iraq, and poured yet more billions into ‘Homeland Defense’ while showing a callous disregard for civil liberties, the rights of the accused, and the views of America’s traditional allies.” Moreover, Cumings accuses America of seeking to establish “hegemony” over other nations by having “expanded [its] militarized structure to its farthest extent in history.”

Cumings summarizes his low regard for America as follows: “It has long seemed to me that we are ill-fitted to be a global superpower … because we are backward compared to our allies in Europe and Japan. Our allies have fashioned a pattern of modern urban life that is deeply satisfying to most of the citizens who live it, because it is exciting and interesting, and buttressed by critical social safeguards for the infirm or the unemployed or the elderly…. In Europe … political leaders not only come from the generation of the 1960s, but represent much of what people were working toward then as goals — civil rights, women’s rights, a better environment, a safety net for the poor. Successive Republican administrations since 1968 have been fighting that legacy …”