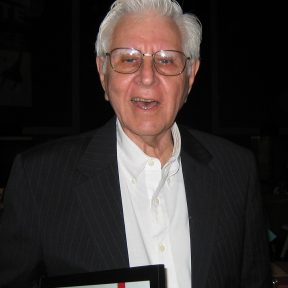

Rodolfo Acuna

Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Author of Photo: RockeroOverview

* Professor emeritus of Chicano studies at California State University

* Supports the radical group MEChA

Born to Mexican parents in Los Angeles on May 18, 1932, Rodolfo Acuña attended Los Angeles State College (now called California State University at Los Angeles), where he earned a BA in social sciences (1957), a General Education Credential (1958), and Master’s Degree in history (1962).

In 1961 Acuña was involved in the Latin American Civic Association, an organization that aimed to improve educational opportunities and establish head-start programs for Mexican American youth. Later in the 1960s he published two elementary-school books and a high-school/community-college text on Mexican American History. Acuña also taught Mexican American Studies classes at Mount Saint Mary’s University and Dominguez Hills State College. In 1968 he received a doctorate in Latin American Studies from the University of Southern California.

In 1969 Acuña established America’s first Chicana/o Studies Department at San Fernando Valley State College (now called California State University at Northridge, or CSUN), where he subsequently spent many years on the faculty. Because his Chicana/o Studies program is both the oldest and largest of its kind in any U.S. school, Acuña is widely regarded as the “Father of Chicano Studies.”

“A primary objective” of Acuña’s Chicana/o Studies Department is “to assist in the development of analytical and communication skills of students,” so as to “prepare [them] for careers in an increasingly competitive labor market and graduate/professional school opportunities …” Moreover, the Department aims to “question colonization and challenge [the] Eurocentric perspectives and racism” that allegedly pervade not only academia, but American society at large.

Underlying Acuña’s curriculum is the separatist belief, candidly expressed on the Department’s website and in its literature, that “minority students are culturally, linguistically, socially, and educationally different” from other students. Acuña traces this divide to the fact, as he sees it, that the U.S. annihilated millions of indigenous people and usurped approximately half of Mexico by force. He further contends that Chicanos continue to be oppressed in American society, whose intractable injustices must be combated by any means necessary, including violence. “Chicanos have to get a lot more militant about defending our rights,” says Acuña.

In a 1993 demonstration by Latino students at Cal State Northridge, Acuña said: “You are living in Nazi U.S. We can’t let them take us to those intellectual ovens.” In the ’90s as well, Acuña condemned supporters of California’s Proposition 187) (a 1994 ballot initiative that sought to prohibit illegal aliens from accessing non-emergency social services) and Proposition 209 (a 1996 ballot initiative banning race and gender preferences from California’s public agencies and universities). “Anyone who’s supporting 209 is a racist and anybody who supports 187 is a racist,” he claimed. On another occasion, Acuña further expressed his contempt for America by asserting that “the [demise] of the Soviet Union was a tragedy for us [Chicanos].”

Exhorting his students “to critically think about identity,” Acuña urges them to reject words like “Latino” because “it is a term that has been imposed upon us.” Such themes trace their origins to Acuña’s 1972 book, Occupied America: A History of Chicanos. Now the most widely assigned text in Chicano Studies programs across the United States, this volume includes such chapter titles as: “Legacy of Hate: The Conquest of Mexico’s Northwest”; “Remember the Alamo: The Colonization of Texas”; “Freedom in a Cage: The Colonization of New Mexico”; “Sonora Invaded: The Occupation of Arizona”; and “California Lost: America for Anglo Americans.”

Also in Occupied America, Acuña writes that “Mexicans—Chicanos—in the United States today are an oppressed people” whose “citizenship is second-class at best”; who “are exploited and manipulated by those with more power”; and who “sadly … believe that the only way to get along in Anglo-America is to become ‘Americanized’ themselves.” The author adds that “Anglo control of Mexico’s northwest territory is an occupation of a part of the American hemisphere,” and that “the parallels between the Chicanos’ experience in the United States and the colonization of other Third World peoples are too similar to dismiss.” For example:

- “The land of one people is invaded by people from another country, who later use military force to gain and maintain control.”

- “The original inhabitants become subjects of the conquerors involuntarily.”

- “The conquered have an alien culture and government imposed upon them.”

- “The conquered become the victims of racism and cultural genocide and are relegated to a submerged status.”

- “The conquered are rendered politically and economically powerless.”

In 1989 Acuña was a founder of the Labor/Community Strategy Center, an anti-corporate “think tank/act tank” and a “school for organizers” who are “committed to building democratic international social movements.”

Acuña has tried to duplicate some features of his own CSUN Chicana/o Studies Department at other universities. His most ambitious attempt came in 1990, when he applied for a position in the Chicano Studies Department of the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB). When the Department turned him down because of his “fiery brand of advocacy” and his “weak scholarship,” Acuña in 1992 filed a “racial, political and age discrimination” lawsuit against the University of California Regents, ultimately winning a $326,000 settlement in 1995. But when the presiding judge refused to force UCSB to hire Acuña, the professor accused him, on no specific evidence, of “anti-Mexican bias.”

In 1993 Acuña supported a sit-in/hunger strike where nine people were protesting the refusal of UCLA’s Chancellor to give his school’s Chicana/o Studies Department the same status as traditional academic departments.

Over the years, Acuña has enthusiastically welcomed radical Chicano groups to his CSUN campus, most notably MEChA, for which Acuña has served as an adviser. In November of 1996, Acuña played a pivotal role in making CSUN the site of MEChA’s annual conference, an event that was keynoted by Acuña himself.

In April 2003 Acuña delivered a keynote speech at a CSUN student-union event honoring the late United Farm Workers leader Caesar Chavez.

Acuña objected to President Barack Obama’s November 2014 executive action on immigration, known as Deferred Action for Parental Accountability (CAPA), which authorized the granting of work permits, tax rebates, Social Security cards, and protection from deportation, to millions of illegal immigrants. In an ope-ed published by the L.A. Progressive, Acuña complained that the president’s action did not go far enough: “Obama’s plan limited it to undocumented parents who had children that were born in the United States—the parents of the dreamers would not be protected, and the order will only be in effect for as long as Obama is president.”

Acuña maintains his own website and blogs on it frequently.

For additional information on Rodolfo Acuña, click here.

Further Reading: “Biography of Dr. Rodolfo Acuña” (Latinopia.com); “Chicana and Chicano Studies” (CSUN.org); “The Liberated Chicano” (L.A. Weekly, 4-19-2006); “Chicano Student Group Defended” (L.A. Times, 8-30-2003); “Immigration Reform: If It Stinks, Light a Match” (by Rodolfo Acuña, L.A. Progressive, 11-29-2014).